Wage increases result in higher prices: Empirical investigation

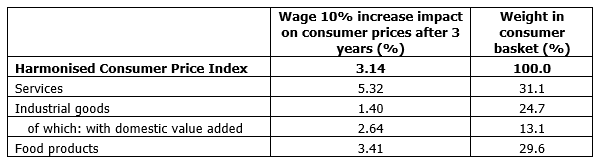

Labour costs are one of the main factors affecting consumer prices of goods and services, according to our recent research*. When the average wage increases by 10%, the consumer price level in Latvia rises by 3% in the medium term; moreover, three fourths of the pass-through take place during the first year after the wage rise.

This article continues an analysis of the characteristics of Latvijas Banka short-term inflation projections model (STIP) – this time regarding the impact of labour costs on consumer prices (for the previous article on the impact of global food commodity prices on consumer prices, see here).

Compensation of employees is an important part of production costs in every firm. Thus, when wages rise, after some time one can also observe increases in consumer prices. However, the impact of labour costs on prices could differ both in time and magnitude for all goods produced and services provided (see Table A1).

Services

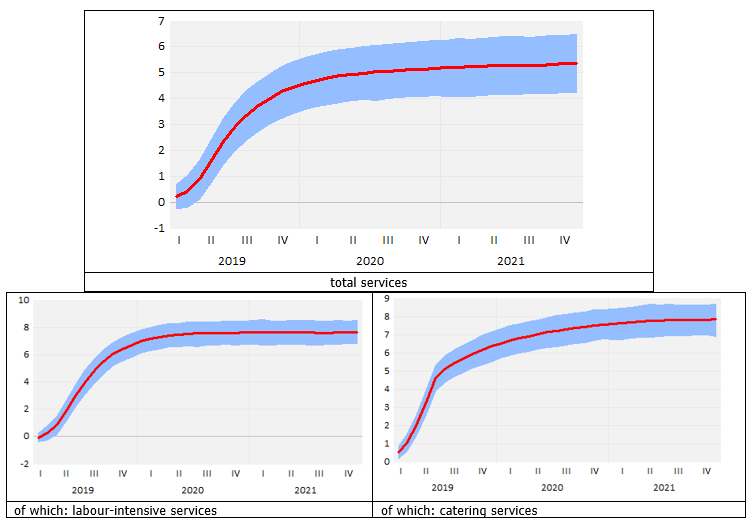

An increase in labour costs has the largest impact on the prices of services, since services provision typically is more labour intensive than the production of goods. When the average wage in the country grows by 10%, services prices increase by more than 5% in the medium term (over three years), and one half of this impact is seen after six months (see Figure 1).

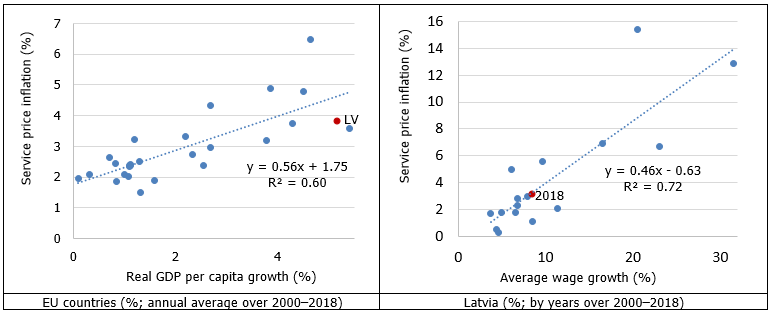

During 2005–2008 – the period of buoyant economic growth and steep wage rises – services prices showed remarkable increases. A strong empirical relation between economic activity and consumer price inflation is evident also in the European Union (EU). Those countries with the fastest economic growth over the last 20 years likewise experienced the steepest rise of services prices (see Figure 2).

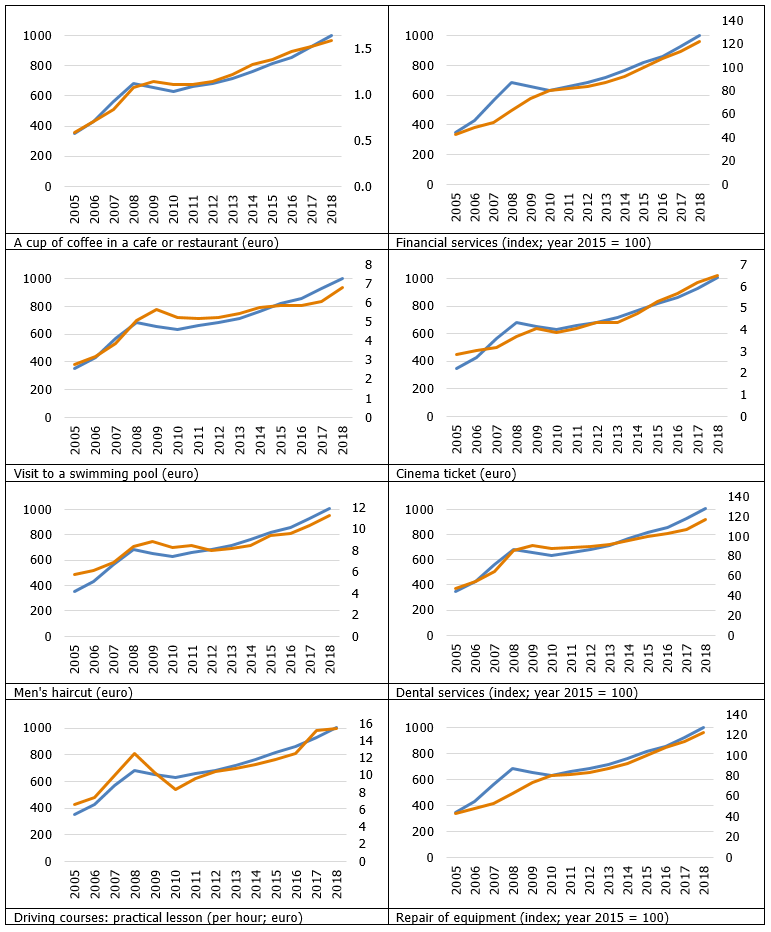

Labour costs are indeed the most important cost component of services. However, various services prices react differently to labour cost developments. For instance, the price elasticity of financial services or a cup of coffee in a restaurant to labour costs is around one. Very high elasticity is also observed for visits to the swimming pool, cinema tickets, as well as dental and haircut services, repair of equipment or driving courses (see Figure A1). Prices of some services are also determined by other factor costs. For instance, it can be clearly seen that the price of a practical driving lesson reacts also to car fuel prices – in 2008 and 2017, the price of driving courses increased faster than it would be determined by the long-run relationship with labour costs (exactly these years were characterised by a steep increase in oil prices and hence car fuel prices). There are also services prices which react to labour costs to various extent. Therefore we divided all services[1] in several groups. We found that the following groups statistically significantly react to developments in wages - catering, communication, accommodation, package holidays and other market services (hereinafter – labour-intensive services).

Labour-intensive services form the largest group of services (see Table A2; more than 40% of total services) that share a common price dynamics and very high price elasticity to labour costs. When the average wage in Latvia grows by 10%, the prices of labour-intensive services increase by 7.5%. Similarly, catering services also display high price elasticity (their share in total services is almost 20%).Yet, prices in cafes obviously depend also on developments in food prices.

Figure 1. Pass-through of a 10% increase in labour costs to consumer prices of services in Latvia (%)

Notes: estimates are made over the 2005–2018 period, using monthly data; the simulation assumes a permanent average wage rise by 10% as from January 2019. The red line shows the average and the bands show a 68% confidence interval.

Figure 2. Relationship between domestic economic activity indicators and consumer prices of services

Notes: figure on the left excludes Ireland as outlier; figure on the right excludes years 2009 and 2010.

Prices of other services react less or have no reaction to increases in Latvian labour costs. For instance, prices of accommodation services, largely determined by demand and supply interactions, are reflected in a hotel room occupancy rate. Prices of a hotel room tend to rise with an increasing inflow of tourists and vice versa – high rates of unfilled rooms may intensify price competition among hotels and drive prices downwards. Prices of air transport are typically driven by labour costs and fuel prices. According to IATA – the International Air Transport Association – 25% of total operating expenses in global airline industry are determined by fuel costs and 23% are determined by labour costs[2]. However, in Latvia air transport prices react to domestic labour costs substantially weaker than to fuel prices. This might reflect the fact that labour costs in aviation are largely determined internationally and therefore might not mirror directly the domestic wage developments. The competition is also quite fierce in the Latvian market – from 2014 through 2018, air transport prices in Latvia have dropped by 32% compared to a moderate increase in the euro area (7%) and the Baltic States (a firm increase in Estonia by 12% and a slight decrease in Lithuania by 4%).

Prices of package holidays are to some extent driven by labour costs. But they are also affected by prices of air transport, as package holidays are defined as holidays where the cost of travel and accommodation are bundled in one price.

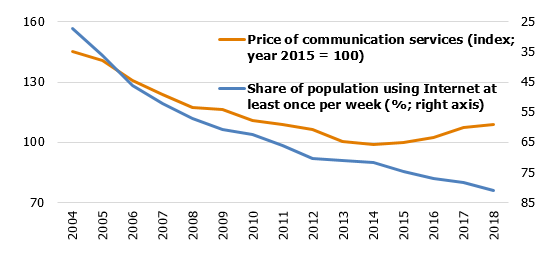

Finally, prices of communication services are substantially affected by the adoption of technical innovations and the increasing number of clients. Prices of communication services decreased considerably over the last 15 years, and during this period the number of Internet users significantly increased (see Figure A2). The cause and effect relationship is most probably bilateral in this case – the large number of Internet users lowered the maintenance costs of Internet infrastructure per client, fostering availability of Internet at a lower price. Internet access at a lower price, in turn, attracted even a larger number of internet users.

Industrial goods

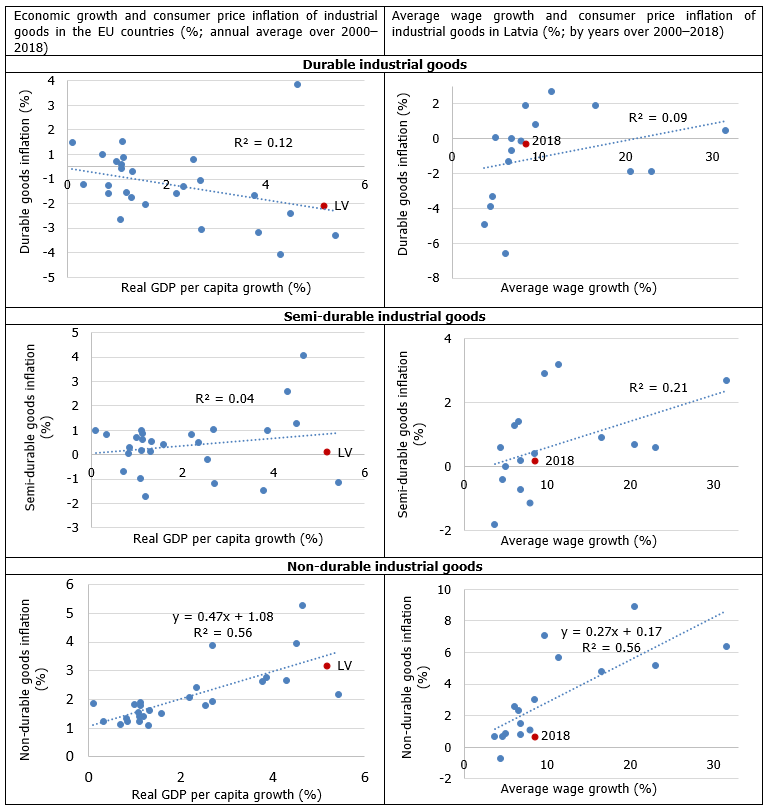

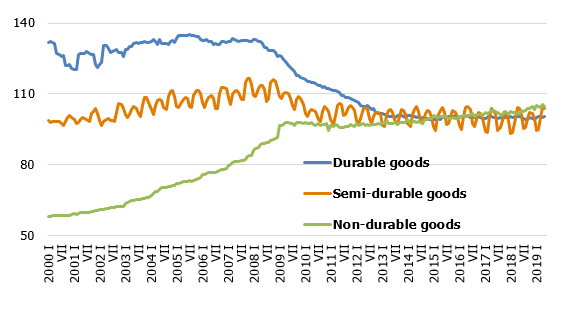

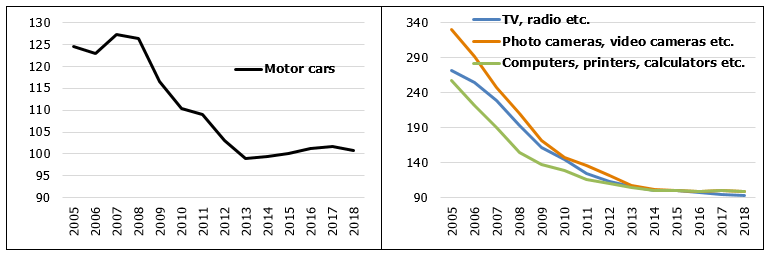

Various industrial goods show very different price trends. Consumer prices of durable goods (motor cars, refrigerators, etc.) tend to decrease over time (see Figures A3 and A4). The lion's share of these goods is imported[3] and their prices depend mainly on the euro exchange rate and such hardly measurable factors as the global technical progress or increasing integration of developing countries with low labour costs in global value chains. Moreover, the pass-through of the exchange rate to prices is quite ambiguous and depends on the interaction between demand and supply of a particular product as well as on the importer's price formation strategy in the respective country (for instance, whether the importer sets the price in local currency or the producer's currency). Therefore, prices of durable industrial goods typically react slowly to labour costs, as the impact is hardly traceable and may often vanish through long global value chains.

Consumer prices of semi-durable goods (clothing, footwear, etc.) show considerable seasonality and the price level on average has remained almost unchanged over many years. Although clothing production in Latvia is gradually becoming costly due to rising labour costs, the availability of cheap imports counterbalances its impact on clothing consumer prices.

In turn, consumer prices of non-durable industrial goods (soap, newspapers, medicines, etc.) tend to rise over time. The share of imported goods here is considerably lower and this is the only group of industrial goods, where prices significantly correlate with domestic economic activity both in Latvia and the EU (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Relation between domestic economic activity indicators and consumer prices of industrial goods

Notes: figure on the left excludes Ireland as outlier; figure on the right excludes years 2009 and 2010.

By means of factor analysis, we selected those industrial goods prices which correlate with domestic labour costs (hereinafter – industrial goods with domestic value added[4]. These goods account for more than a half of consumer spending on industrial goods. When the average wage in the country rises by 10%, the consumer prices of industrial goods with domestic value added increase by almost 3% (see Figure 4). The elasticity of industrial goods prices to labour costs is considerably lower than in case of services, because raw materials and intermediate goods account for a large share of its production costs (and, respectively, labour costs have a lower share). The pass-through of labour costs to consumer prices of industrial goods with domestic value added also takes longer time – one half of the impact is observed after one year, reflecting a relatively long expiry date for industrial goods.

Figure 4. Pass-through of a 10% increase in labour costs to consumer prices of industrial goods with domestic value added in Latvia (%)

Notes: estimates are made over the 2005–2018 period, using monthly data; the simulation assumes a permanent average wage rise by 10% as from January 2019. The red line shows the average and the bands show a 68% confidence interval.

Food

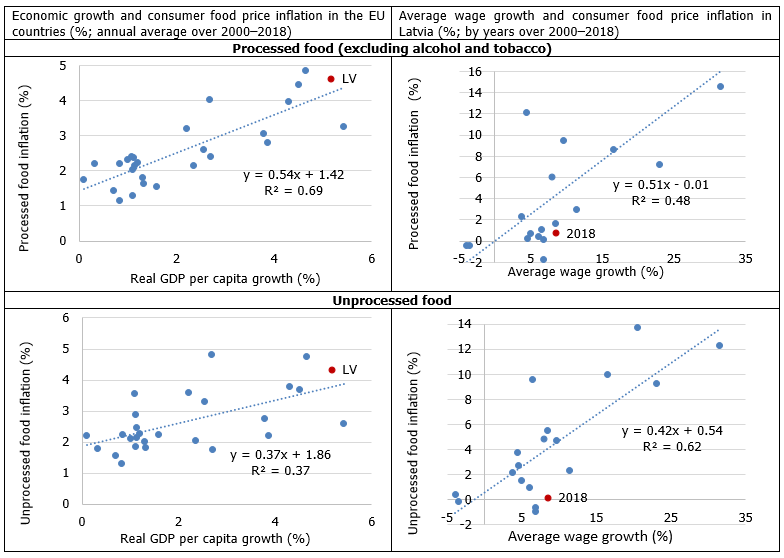

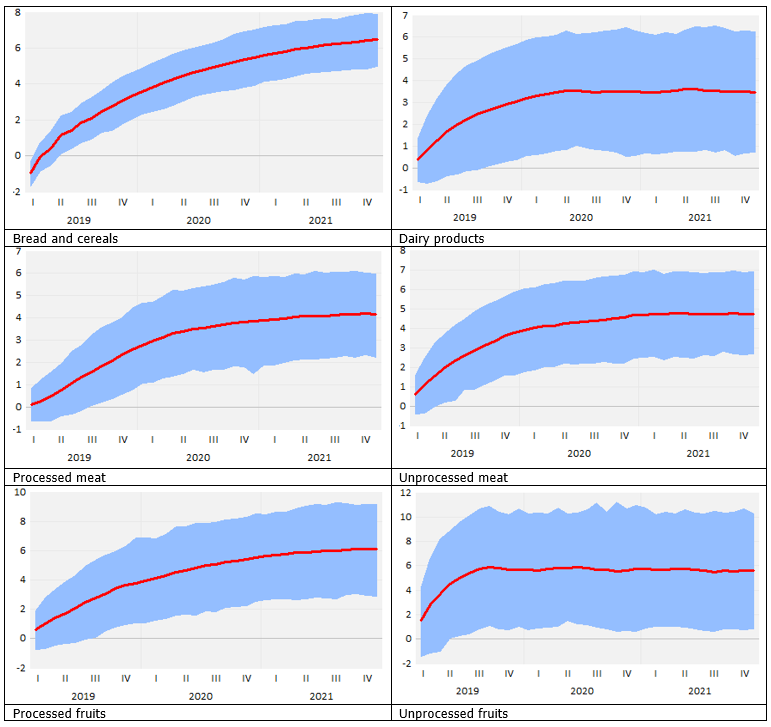

Consumer prices of food products on average increase by 4% in response to a 10% increase in wages. Therefore, domestic labour costs are an important driver of food consumer price inflation as well as global prices of food commodities. Prices of both processed and unprocessed food show high correlation rates with domestic economic activity (see Figure 5). The longer the expiry date of a product, the more moderate the speed of the pass-through. For instance, half of the impact of labour costs on unprocessed fruits is already evident after two months, on dairy products – five months, on processed meat products – nine months, while on cereal products – 11 months (see Figure 6).

Figure 5. Relationship between domestic economic activity and consumer food prices

Notes: figure on the left excludes Ireland as outlier; figure on the right excludes years 2009 and 2010.

Figure 6. Pass-through of a 10% increase in labour costs to selected consumer food prices in Latvia (%)

Notes: estimates are made over the 2005–2018 period, using monthly data; the simulation assumes a permanent average wage rise by 10% as from January 2019. The red line shows the average and the bands show a 68% confidence interval.

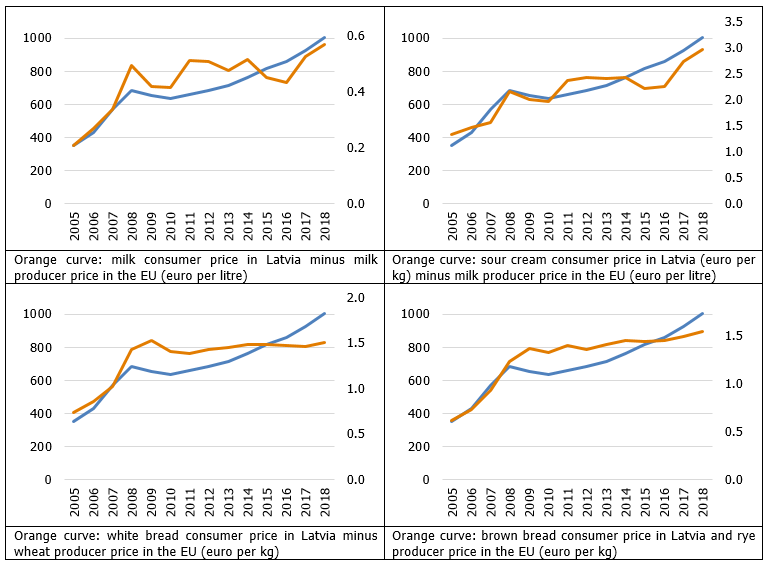

The impact of labour costs on consumer food prices in Latvia is also clearly seen at more detailed product level. The gap between the consumer price of a particular food product in Latvia and the global food commodity price widens exactly on occasions when wages face strong growth. For instance, the dynamics of labour costs in Latvia describes well why the retail price of sour cream in the long run rises faster than producer prices of milk. Increasing labour costs also give an answer why the prices of white bread in a supermarket correlate more with the rises rather than decreases of wheat producer prices (see Figure A5).

Conclusion

There is often a tendency to believe that domestic economic activity affects only "core inflation"[5] which itself is understood as the prices of services and non-energy industrial goods. Our study shows that such a view is not truly correct. First, several "core inflation" components do not react to domestic economic activity (e.g. durable industrial goods which are imported – motor cars, refrigerators, etc.). Second, many inflation components outside the canonical definition of core inflation significantly react to economic activity (e.g. processed and unprocessed food prices). Furthermore, labour costs are equally important drivers of food consumer prices as well as the global food commodity prices.

We also show that the reactions of different goods and services prices to domestic labour costs differ both in magnitude and speed. Services typically are more labour-intensive than goods, therefore they react stronger to labour cost developments. In turn, the speed of a pass-through depends on the product expiry date: the shorter the expiry date is, the faster the pass-through.

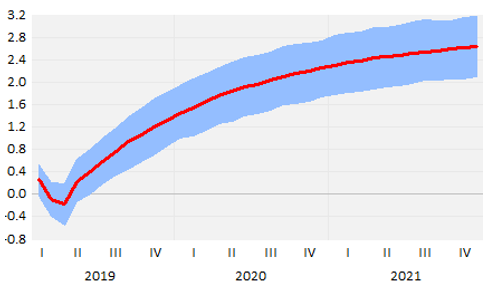

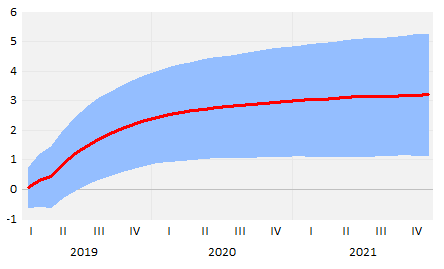

Finally, we estimate that the pass-through of a 10% increase in labour costs tend to push up consumer prices in Latvia by more than 3% in the medium term (see Figure 7). This conclusion has an important role in the formation of inflation projections. Besides, our study could be employed analysing inflation dynamics in cases when there are steep rises in minimum wages or in public sector wages.

Figure 7. Pass-through of a 10% increase in labour costs to consumer prices in Latvia (%)

Notes: estimates are made over the 2005–2018 period, using monthly data; the simulation assumes a permanent average wage rise by 10% as from January 2019. The red line shows the average and the bands show a 68% confidence interval.

Appendix

Table A1. Pass-through of a 10% increase in labour costs to consumer prices after three years (%)

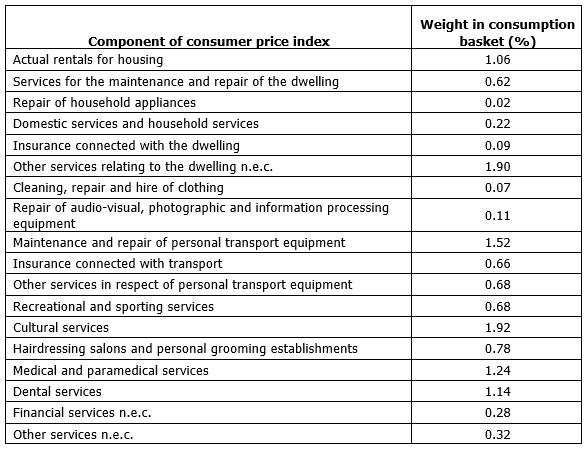

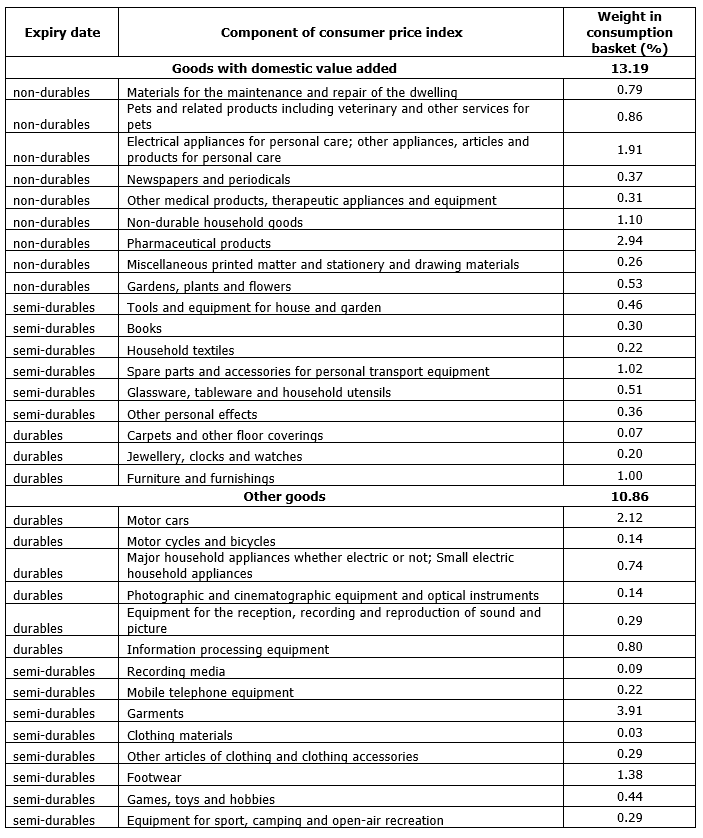

Table A2. Components of Harmonised Consumer Price Index that were included in the aggregate "Labour-intensive services"

Table A3. Division of industrial goods on those with a considerable domestic value added and other goods

Figure A1. Average monthly gross wage (blue) and consumer prices of selected services in Latvia (orange; right axis)

Figure A2. Communication service prices and number of Internet users

Figure A3. Consumer prices of industrial goods in Latvia by product groups (index; year 2015 = 100)

Figure A4. Consumer prices of selected durable industrial goods in Latvia (index; year 2015 = 100)

Figure A5. Average monthly gross wage (euro; blue) and the difference between consumer prices of selected food products in Latvia and corresponding food commodity producer price in the EU (orange; euro; right axis)

* This article is based on research developed by Latvijas Banka experts, the full version will be published later.

[1] Excluding administered prices.

[2] https://www.iata.org/publications/economics/Reports/Industry-Econ-Performance/Airline-Industry-Economic-Performance-Jun19-Report.pdf

[3] Precise import share is not known, since products imported to Latvia could then be re-exported to other countries.

[4] This definition does not necessarily mean that these products are made in Latvia. The definition rather reflects correlation with domestic labour costs, which might represent domestic value added of the product.

[5] Consumer price inflation, excluding food and energy.

Textual error

«… …»