The tale of four different exchange rate experiences revisited

Morten Hansen has this very good idea of comparing countries with recent nominal devaluations (Iceland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom) with Latvia, which, of course, kept its nominal exchange rate peg unchanged. Given the different exchange rate developments, it is interesting to see whether this has had any implications on the export performance in these countries?

Morten's conclusion is that, despite nominal devaluation, Sweden and the UK still lags behind Latvia in terms of recent export growth. Iceland, however, seems to outperform Latvia. So maybe, just maybe, devaluation can improve export performance?

Well, maybe not. Morten is using data on exports that are expressed in each country's national currency. So nominal devaluation by default leads to rising export values, even though real export figures may have not changed that much at all. Say, if Iceland was exporting one unit of "something" to Europe for a price of 100 EUR at the beginning of 2008, and it still exports this one unit of "something" now and it still has a price of 100 EUR, country's exports statistics in national currency would treat this as a rise in exports (and improvements in competitiveness) only because the exchange rate of the Iceland's kronur against the euro has come down from 90 to around 170 in the meantime (so in the national currency terms, Iceland's exports would have increased from 9000 to 17 000 during this period). Getting more of the less-valuable domestic currency for the same amount of foreign currency, while not exporting more of the actual goods, is hardly a success story and certainly not a sign that your competitiveness has improved.

So better use one common denominator for all cross-country comparisons, for example the euro. Calculate all export figures for each country in euro, and you will see a true measure of competitiveness. If a country's exports are rising in euro terms (and preferably rising faster that everybody else's), you can be pretty sure this is the real deal, not the result of its currency getting weaker[1].

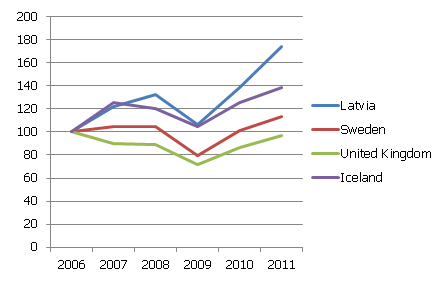

Fortunately, the Eurostat has the exact data we need[2]. Now, comparing all countries' exports in euro, and looking on how they have performed since 2006, we get the following picture for goods…

Figure 1. Exports of goods (euro denominated), 2006=100

Source: Eurostat

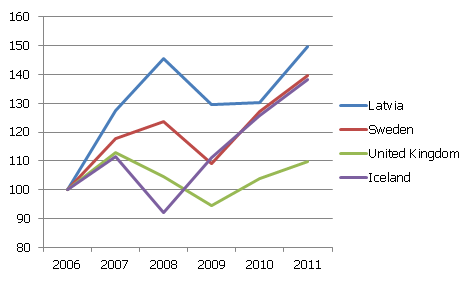

… and services…

Figure 2. Exports of services (euro denominated), 2006=100

Source: Eurostat

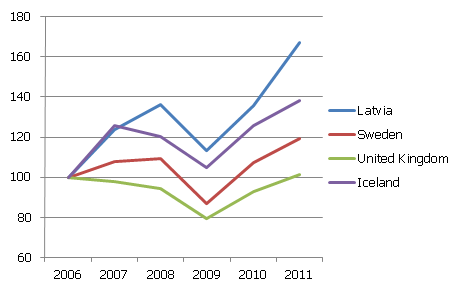

… and combining the two…

Figure 3. Exports of goods and services (euro denominated), 2006=100

Source: Eurostat

One part of Morten's conclusions certainly still holds. Latvia is outperforming both Sweden and the UK in terms of its exports performance since 2006. But you know, now it is also outperforming Iceland, and significantly so. All this achieved without a nominal devaluation. Hence, Latvia is not your typical textbook example, viewed from this angle. Also, the idea that by devaluating your currency you can boost your exports does not hold at all, at least with these data and in this sample of countries.

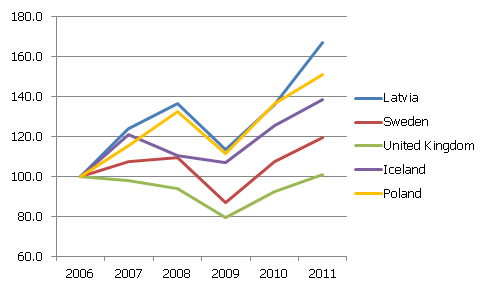

Update: Included Poland in the graph. Does not matter. Latvia is still on top.

Figure 4. Exports of goods and services (euro denominated), 2006=100

[1] One could, of course, argue that data in national currencies are still good and usable, provided they are deflated properly. But properly estimating price deflators is a somewhat tricky (and not always precise) exercise. So in theory, using price-adjusted data should be as good as using data expressed in a common currency. In practice, it almost never is.

Textual error

«… …»