A million dollar question: what the future money will be like?

Technologies inevitably change our daily lives, including execution of payments. Currently, nobody is surprised for opportunities to pay for goods and services both with the traditional cash and payment cards that have already become the order of the day. As projected by many people and institutions, the day when cash will disappear from circulation for good and all payments will be made digitally is unavoidable. For instance, China – a front-runner in a race for switch-over to non-cash payments only – maintains that an entire generation has grown up now, and a large proportion of this generation has never seen cash.

It is natural that in Latvia the generation which has experienced numerous monetary reforms at first hand, when Latvia was still part of the Soviet Union, is rather reserved towards any fundamental changes related to money and its role. Also, in the world at large, all issues that can affect money and its value are treated with great caution, and it is with good reason that central banks playing a determining role in influencing the value of money rank among the most conservative institutions in any country. Society in Latvia and elsewhere does not like overly rapid changes in the field that can directly affect its welfare today and tomorrow in the light of the strong dependence of growth on changes in the value of money.

Therefore, it is all the more important to understand at an early stage the meaning of the current technological changes concerning money and its use, i.e. whether efforts towards an increased digitalisation of payments are just another way of making our everyday lives more comfortable or they will be accompanied by more fundamental changes in the entire current financial system. Will these changes also alter our understanding of money? There are many questions, but few clear answers so far...

Will cash disappear in the future?

The emergence of new payment opportunities has inevitably reduced the use of cash on a daily basis. However, can we project disappearance of cash in the near future based on the forecasts that point to the continuation of the current trends? At present, there are no indications pointing in that direction.

Chart 1. Cash in circulation (% of GDP)

Sources: IMF, LB, ECB, Riksbank.

As illustrated by Chart 1, cash is the least used means of payment in Sweden, which is a European country. The amount of cash vis-à-vis the size of the economy has notably decreased over the past 20 years, i.e. the use of cash has dropped around four times. However, even in Sweden, where the disappearance of cash has been projected in the near future, it has stabilised at this (undeniably) low level over the most recent years. There are obviously reasons why cash remains in circulation despite the increasing availability of the new technologies.

In spite of claims that cash is also disappearing from circulation in China, it is apparent that cash is far from disappearing completely although the downward trend of its use is apparent. And even if it is possible to live in the largest cities today without using cash, its amount in circulation in the entire country is quite considerable compared with Sweden, for example. Moreover, the increasing opportunities offered by non-cash payments in China include concern about efforts to control people's daily lives more and more. Such prospects do not obviously appear attractive for all throughout the country.

According to statistical data, the trends of using cash in the euro area might seem confusing as data point to growing not declining intensity of cash use. However, it should be noted that the euro as the second most important global currency is also widely used to make payments in non-euro area countries, including cash payments (let us remember our recent history). Consequently, data about the total amount of cash issued do not reflect the extent to which cash is used for making payments by residents of euro are countries. Bearing this aspect in mind, it is clear that cash also remains sufficiently popular means of payment in Europe, and if this trend is following a downward path, its pace is certainly not that fast and is not going to reach the level achieved by Sweden in the near future.

In Latvia, cash figures also show a mixed picture, making it impossible to arrive at robust conclusions. Before the euro changeover, the official amount of cash released in circulation did not reflect its real popularity as euro and dollars were also often used to make private payments. Meanwhile, following the introduction of the euro, a portion of its cash that is actually outside the euro area is also added to Latvia. Moreover, the distribution of the issued cash among euro area countries cannot be determined precisely anymore. Most likely, the actual figure is below that of the official statistics; however, it is relatively high and exceeds the European average. Although data of the survey conducted by Latvijas Banka suggest that the share of cash in day-to-day payments continues on a downward trend, this process is relatively gradual. This leads to a conclusion that cash remains quite poplar in Latvia, and our society cannot be expected to become a cashless society in the near future.

There are many reasons why the population can continue to use cash actively (the above-mentioned privacy concerns, building up contingency reserves, attempts to optimise or avoid taxes, general mistrust in public institutions, etc.). The population is also frequently too slow to change its habits; therefore, rapid changes are not expected to occur in this regard. On the other hand, technological progress and costs related to the circulation, storage and processing of cash will nevertheless continue to serve as motivating factors for reducing the use of cash in the future. It is the progress made in this area that will be the key factor in determining the pace of and level to which the use of cash will decline in the future. There are also a lot of unknowns in this regard for the time being.

Digital payments and digital assets – are they alternatives to the "traditional" money?

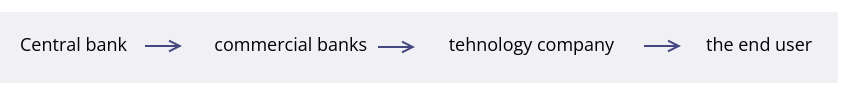

Today, any resident of the country having opened an account with a bank can use opportunities offered by various technology companies in parallel with the traditional means of payment offered by banks (a money transfer, debit card and credit card) to make day-to-day payments, e.g. pay for parking or buy a public transport ticket using a mobile phone, leaving the wallet at home. The account opened with a bank is a critical prerequisite in this regard as payments, despite the technological innovation, are still made in the following order:

To conclude, the official cash issued by central banks remains the unit of account in all processes.

However, the year 2019 marked a real turning point when the technology company Facebook announced its plans to introduce its own private unit of account – Libra, establishing a closed system of payments without involving a central bank and commercial banks. Since the payments made in this system would no longer be automatically converted to dollars, euro or any other official currency, the users of this system would inevitably accumulate these units of account over time, and the need for loans would arise; the value of goods and services would also be measured using the new unit of account within this system. Thus, the Libra would begin to fulfil its functions as real money, but decisions on the amount of money to be released in circulation would be taken by a private company rather than a central bank.

The chance of the emergence of private money was considered as rather unlikely until then; actually, private money is not a brand new and unique concept since the world's history has registered such precedents. It was already more than 200 years ago when monetary units issued by private companies constituted a significant share of the total amount of cash in circulation in the US. However, history has given us ample evidence that the modern centralised monetary system is preferable to any other. Therefore, central banks were taken by surprise and probably slightly shocked by the view that the idea of private money can be considered again and possibly pursued. In the worst case scenario, this might mean that central banks would lose control over the issuance of money and thus also over economic development overall... The Libra project remains an idea only that has not been pursued. The question of whether history can return and we might witness a renaissance of the idea of private money or a decentralised financial system in digital form still remains open. Technological progress offers new possibilities that can help resolve several problems which have made it difficult to expand the use of private money so far.

First, technological possibilities. It was complicated for individuals to create their own money in the past. Currently, everyone having sufficient knowledge of private money can create his/her own cryptocurrency. Gaining public trust is the most complex part of this process, and according to various precedents it is becoming ever more complex as there have been cases when a new cryptocurrency was created to cheat people and disappear with their money.

Second, it was easy to counterfeit private money in the past as it was difficult to check its authenticity, whereas now the situation has changed dramatically since private money is often based on blockchain technology. Any crypto-asset wallet holder can verify the authenticity of the wallet content in the blockchain containing records of all transactions. From time to time, villains misuse people's ignorance and manipulate data that are "sort of" recorded in the blockchain, thus depriving people of various amounts of money. It should be borne in mind that each type of payments and money has its own security specificities you should be aware of not to allow fraudsters to cheat you. Therefore, familiarise yourself with the security specificities of a new type of payment before choosing it.

Private money, in particular where it is used to make payments globally, has several theoretical advantages compared with the traditional money controlled by central banks. First, international payments could be faster, more convenient and also cheaper. Needless to say that it is rather cumbersome to make international payments using the current system. In this case, currency exchange costs would also be lower, thus helping users save some money.

Second, this alternative offered by the private sector might serve as an additional insurance in cases where the policy pursued by central banks leads to a robust upswing in the amount of money in circulation, thus also triggering a rise in inflation and undermining the population's trust in long-term stability of the official money. To highlight the advantages offered by the alternative, it has been proposed to specify the amount of money in circulation using a fixed algorithm as an additional guarantee or, in the strictest case, to specify the maximum possible money limit to be released in circulation. With economic activity and demand, including the demand for money, taking an upward trend, a fixed money supply would inevitably lead to the increase in the value of this money.

Unfortunately, there are several factors at play that currently do not allow the solutions offered by the private sector to be regarded as a fully valid alternative to the existing money. Real money has to perform the functions of a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value. Therefore, even assuming that the offers from the private sector can make payments as convenient, fast and cheap as possible, they are not sufficient to serve as a serious alternative to the current monetary system.

The first problem relates to the function of a unit of account. The traditional and official money bears significant advantages in this regard. The official money, by definition, means that it is the sole legal tender accepted in transactions with the public sector, including tax payments. As long as taxes are paid in the official monetary units, it will be required to express at least part of payments in this respective money; therefore, it will always be in demand. Private money does not have such "natural" advantages. Hence, it is hard to imagine that somebody might wish to express the value (prices) of goods and services in other units rather than in the official legal tender. Even if individual traders might be interested in this solution to attract new customers, this would mean maintenance of two parallel accounting systems as long as transactions with the public sector remain unchanged. It is expensive and complicated; therefore, it is unlikely that this solution will be widely used.

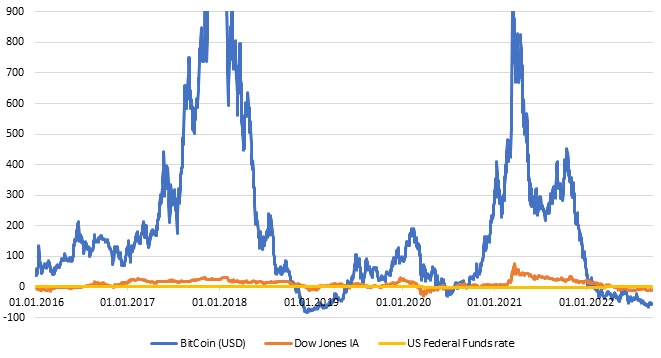

Chart 2. Bitcoin, stocks, money market rate (annual changes; %)

Second, private money entails serious problems with regard to its potential use as a store of value. When conducting payments in a closed system, it is inevitable that some users will accumulate funds more quickly than they will be spent and some will have to borrow, for example, to cover contingent payments. For people to be willing to build up savings in any unit of account, however, the ability of rational future planning is critically important or at least sufficient stability when we can reasonably hope that our savings are not going to become completely valueless at some point. However, as can be seen in Chart 2, the value of Bitcoin, one of the most popular digital currencies, is so volatile that even stocks which are considered one of the riskiest types of investment and savings for people who cannot really call themselves market experts seem relatively stable. Against this background, the value of traditional money, inter alia affected by the central bank's decisions on policy rates, looks like a straight line – perfectly stable. Given the high instability of their value, digital assets clearly have no hope of fully replacing traditional money in the future.

Some experts believe that digital assets have no practical and usable value (as opposed, for example, to gold; even though it may have no application as real money, it can still be used in, say, dentistry), therefore, the value of those digital "currencies" is an absolute zero. And, even if this statement turns out to be too categorical and digital assets do have at least some (currently unknown) practical value, this is insufficient to fulfil the functions of real money. The question of how the monetary system would be controlled in this case still remains open.

First, contrary to the current system where central banks are in charge of the monetary stability, they have clearly-defined goals and objectives, and the system supervisors are also publicly known, the true objectives and motivation of the supervisors of a private money system would never be completely transparent (public good or higher corporate profits?). Moreover, in some cases (for example, with Bitcoin) no information on these persons is publicly available. This does not help to believe that the monetary system will be stable and it is reliable in the long term. Even if the system is controlled by an algorithm, no matter how complicated, it can never foresee all surprises and unexpected shocks that the system may have to face, whose addressing requires human judgement [1].

Second, a daily control over money is insufficient for any monetary and financial system to be really functional. The ability to provide support (liquidity) in a crisis to participants facing temporary payment problems and having no opportunities to borrow from other system participants (access to a lender of last resort) is equally important. In the absence of this opportunity, a system is unstable and may collapse when hit by the first unexpected turbulences. Providing this support inevitably involves a subjective judgement; therefore, even the most scrupulous regulation even in theory could hardly prevent situations where assistance is or is not provided based on short-term business interests rather than system stability and sustainability considerations (for example, granting a loan to a competitor versus allowing it to go bankrupt and then buying over at a low price).

Overall, the technological progress will surely continue to also affect the payment solutions developed by the private sector, but, at the moment, it is hard to see how these payment solutions could become something more and start fully replacing the existing money. If the control of a monetary system depended merely on technical equations and algorithms, the private sector would, no doubt, be able to find a much more effective solution than the state. Control and management of money, however, will always involve also subjective decisions and judgements that can be made by humans only; therefore, trusting those people and their true objectives is critically important for the system to be functional. Public institutions have significant advantages in this sense, and they are not going to lose their prominence over time. Hence, there are currently no worthy alternatives to a monetary system controlled by the central banks.

Nevertheless, the private sector still has a prominent role in this system, as commercial banks provide access to non-cash for the end users – the population and businesses of a country. In theory, the central banks could retain their role as "an anchor" of the overall monetary system, while the role of the intermediary accessing the end user in parallel to commercial banks (or, in extreme cases, replacing them) could also be undertaken by other market players. The new technologies theoretically allow it. The question is whether it is really necessary and what are the benefits for the population.

What is the role of the central bank digital currencies?

A digital currency created by the central banks would be a third form of money in addition to cash and non-cash payment means provided to population through banks. In theory, end users would enjoy essentially the same access to the central bank digital currency as currently to non-cash payments. The central bank would create and maintain a system, whereby supervised intermediaries would provide the central bank digital money to the end users. This dissemination model is already operational in Nigeria and the Bahamas, the leaders in the creation of the central bank digital money. The most significant changes would affect the so-called back-office layer of the system. Although provided to the end user by an intermediary, the central bank digital money is a means of payment similar to cash, just digital in form, issued and backed by the central bank. System participants or intermediaries supervised by the central bank, in turn, would be able to use the system for offering more friendly and innovative payment solutions to their customers.

Looking at the potential of the central bank digital currency, there are clearly the following (theoretical) benefits:

- it would enable system users to create new more efficient and user-friendly payment opportunities without relying on just a few big global market players currently dominating individual market segments;

- the central bank involvement would offer additional opportunities for improving the privacy level of payments and personal data protection;

- this money would provide significant benefits also from the perspective of security, ensuring central bank backing for the funds.

There are, however, also serious problems involved, and currently several central banks are trying to figure out whether the potential benefits of such currency would outweigh the possible risks. First, new additional payment solutions would make the whole payment system much more complicated, and such a system would hardly be more beneficial (as well as cheaper) for both traders and the population.

Second, it is quite unclear how new alternatives to the existing system could be created without significantly weakening that system. Since the establishment of the current system, commercial banks have been the main element of this system serving as a link between the policymakers (central banks) and end users (population and businesses). A solid banking system whose stability, in turn, is largely dependent on the accessibility and stability of bank financing has always been an important prerequisite for a smooth and successful central bank policy transmission to the economy. A broad stock of deposits has so far been considered one of the main sources of stable bank financing, also largely providing for lending to the economy. As can be seen in Chart 3, Sweden differs greatly from the euro area average in this sense, as bank deposits account for only about 2/3 of the required financing for lending, while in the euro area lending, on average, was almost entirely financed from deposits for a long time. Following the excesses observed at the beginning of the 21st century, currently the deposits received are much larger than loans granted in Latvia due to the cautious approach pursued by banks.

Chart 3. Loan-to-deposit ratio in banks

Source: ECB SDW.

At the same time, if the central bank digital currency meant a possibility to open an account for storing the central bank money, there would be a high probability of at least a partial outflow of private money deposits from commercial banks. That could cause financial stability problems in banks and a subsequent further deceleration of lending. From the cyclical perspective this may not always be a problem, however from the structural perspective factors limiting access to financing in the economy would inevitably be detrimental to long-term growth. Therefore, here the balance between the long-term gains and losses is unclear. One can, of course, try to reduce the potential negative side-effects by setting restrictions and limits on the use of this digital money, but then it is unclear whether at all and how big the demand for such central bank money with limited usage opportunities would be.

Third, at the current juncture, it is unclear whether such an alternative offered by the central bank would support or, on the contrary, limit financial innovations. The entry of a significant public institution in the market creates questions whether such a step is consistent with the free market principles which are binding on all EU central banks, including the ECB. An additional complication is the fact that, in parallel to the attempts of creating a new payment alternative, Europe is also engaged in payment system reforms aimed at making the existing system more open to competition and innovations. Provided that these reforms are successful, the development of an alternative system seems unnecessary. At the same time, the working on alternatives may raise concerns that the ongoing reforms would not produce the expected results... It must be borne in mind that currently the above-mentioned solutions are just being researched and could be implemented in a more distant future. Therefore, an improvement of the existing payment infrastructure and facilitation of respective innovations is presently also a large step forward in making our everyday life easier. We are used to quick and relatively cheap payments in Latvia, but in many places in Europe the journey to where we are standing right now would still take some time. Therefore, the review of both the Payment Service Directive (PSD) and Settlement Finality Directive (SFD) could facilitate innovations and result in new types of payment. It is often obvious that directives and regulations of this type limit the emergence of true innovations by putting them into a certain frame. At the same time, an absolute discretion in this regard is also unthinkable.

There are many unclear questions concerning the central bank digital currencies, and that explains why there is no overly rush in this respect. Many countries (for example, Sweden) have already started the testing of various solutions, while others (including the ECB) are still at the stage of theoretical examination. This subject is also widely discussed and researched by experts, and the level of enthusiasm regarding the central bank digital currencies could be viewed as low. It will be a real challenge to come up with a solution that avoids central bank digital currencies turning into (in the words of the senior research fellow of the Centre for European Reform Zach Meyers) an expensive failure.

There is but one main conclusion: any money-related issue concerns all of us; moreover, any change may bring about serious long-term consequences affecting the welfare of every individual. Therefore, any reforms should be carefully considered. On the one hand, the technological progress opens up wide opportunities also in the field of money creation and use, whereas, on the other hand, everything that concerns money has always been conservative, and rightly so. How do we find the right balance and whether such balance even exists will be discussed at this year's conference of Latvijas Banka on 3 November.

[1] For example, along with a rise in the value of money, by definition, the maximum number of Bitcoins that can be issued also means a fall in all other prices or deflation, which is definitely unhealthy in the context of economic growth.

Textual error

«… …»