The indirect impact of oil prices on inflation in Latvia

In 2015, the drop in oil prices reached 47%, and prices continued to drop at the beginning of 2016 as well. At the end of 2016, however, – after negotiations among the most important players in the international oil market – the trend of rising oil prices became pronounced. Such changes in oil prices affect the Latvian inflation level in two ways:

- directly (by changing the price of fuel, as well as heating and natural gas tariffs);

- indirectly (by raising/diminishing production costs of goods and services and thus also their prices).

Latvian consumers feel the direct impact rather quickly (for instance, 85% of the increase/decrease in oil price is reflected in the prices of gasoline and diesel fuel in about two months) [1]. Yet the adjustment of the prices of goods and services can take some time while entrepreneurs transfer energy price changes to selling prices. It is precisely the evaluation of the impact of this indirect effect that we will discuss in this article.

Channels of indirect effect

Oil price fluctuations the most affect costs of those goods and services, which more intensively use energy products in the production process, thus creating an indirect pressure on the prices of these goods or services.

At the same time, changes in energy product prices can influence domestic demand for other goods and services. For instance, as a result of the diminished price of oil, households may save extra money, which they can spend later on other goods and services. To a certain extent, it can compensate the impact of the indirect effect.

Assessing these interconnections is a rather complicated process not least because the degree of pass-through of oil prices depends on several factors:

- state of the economy (whether it performs above or below its potential);

- degree of competition in the domestic market (the keener the competition, the more elastic are the prices);

- possible asymmetry of oil price changes (if entrepreneurs react differently to the increase and decrease in costs, determining the prices of goods produced).

Moreover, the indirect effect becomes pronounced over a longer period of time, for entrepreneurs need time to adjust prices to the new cost conditions.

Indirect effect on prices by Latvian economic sector

To determine, which prices of particular groups of goods and services are indirectly impacted by oil prices the most, we used the Latvian computable general equilibrium model based on input-output table [2].

This table contains data that reflect the interconnections between different sectors of the economy and the structure of their intermediate consumption. This method thus allows to identify those sectors (and those goods and services), which, in the production process, use energy products most intensively and whose costs really can very much depend on the fluctuations in energy prices.

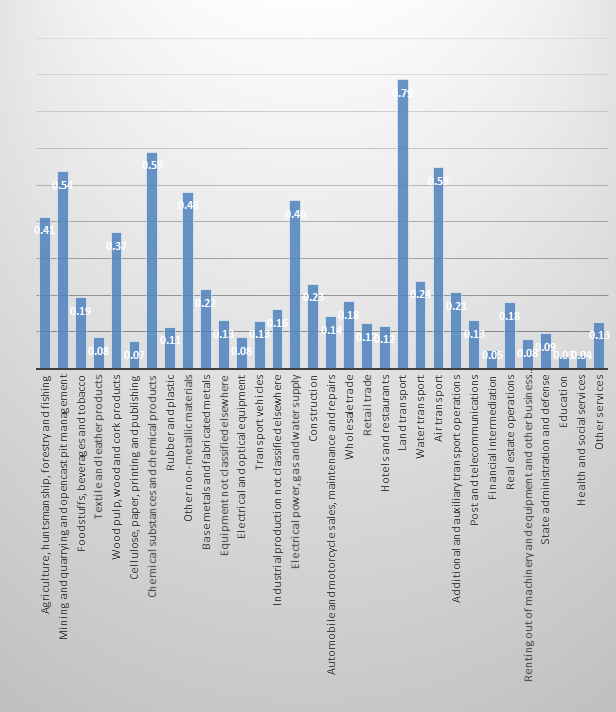

Considering producer prices in a breakdown by sector (Fig. 1), we can conclude that changes in the price of oil have the greatest impact on the prices of land transport and air transport service prices. The explanation is the high energy intensity of these services and the low replaceability of energy products in the production process.

Among the non-energy goods, the effect is greatest in the chemical substances and chemical products sector where oil products are intensively used as raw materials. Energy intensity seems to be relatively high also in Latvian agriculture and mining and quarrying, and the oil price effect is greater relative to other sectors. It should be noted that these estimations are comparable with calculations of other countries where the indirect effect predominates too in the chemical substances and transportation sectors [3].

Figure 1. 10% impact of oil shock on producer prices by sector

Contribution of indirect effect to Latvia's core inflation measured by HICP excluding energy and food

Computable general equilibrium model is static and thus does not account for the fact that production structure can change over time, with producers adjusting to the changes in relative costs of production factors. With this in mind, we used the econometric VAR (Vector autoregression) model to estimate the contribution of the indirect effect of oil price changes to Latvian inflation.

The advantage of this model consists in that it allows to evaluate the above interconnections and impact channels, taking into account the fact that oil price changes can affect production prices and thus, with a delay, consumer prices. The following factors have been included in the model we evaluated:

- BRENT oil price in USD;

- short-term interest rate (EONIA);

- GDP at constant prices;

- unemployment rate;

- nominal effective exchange rate;

- HICP excluding energy and food [4]

To ensure the robustness of results, the model was evaluated over two data samples: 2000Q1-2016Q2 and 2005Q1-2016Q2, including various time lags.

The first data sample reflects the entire available set of data, whereas the second one reflects the period after Latvia's joining the European Union. Altogether, we have evaluated six alternative models, but, in this article, we consider only two: the model that provides a higher (first model) and a model that provides a lower (second model) estimation of the impact of the indirect effect [5].

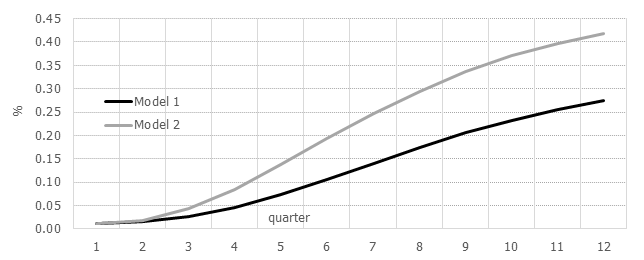

Figure 2 reflects the reaction of the HICP inflation excl. energy and food to the 10% positive oil price shock that follows from these two models. According to our estimates, the initial effect of the oil price is relatively small. It rises faster starting from the fourth quarter after the shock. The explanation could be that in the first quarters the indirect effect is partially compensated by the aforementioned effect of domestic demand, which pulls in the opposite direction. Overall, 10% positive oil price shock causes an 0.3-0.4 percentage point increase in inflation excl. energy and food over a three-year period.

Figure 2. Impact of 10% positive oil price shock on HICP inflation excl. energy and food in Latvia

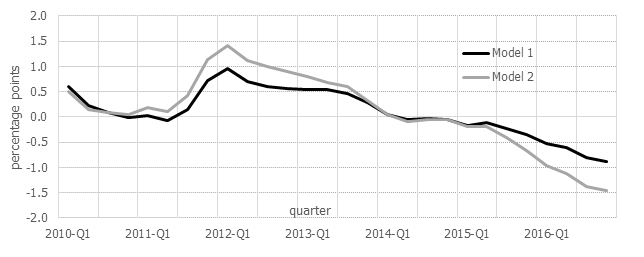

Figure 3 reflects the contribution of the indirect effect to the annual rates of change in HICP excluding energy and food . It indicates that when oil prices change dramatically(for instance, after the crisis, oil prices increased tremendously and, in 2014–2016 they dropped rapidly), the impact of production costs on the prices of goods and services can be considerable. Following the fast drop in the price of oil in 2015, HICP inflation excluding energy and food dropped both in 2015 and, even to a greater extent, in 2016 (due to time lag).

Overall, there is considerable uncertainty regarding the amount of this effect in 2016 between different models, varying between 0.7% to 1.2%. HICP inflation excl. energy and food was 1.2% in 2016. If there were no indirect effects due to the drop in oil price, HICP inflation excl. energy and food would have reached 1.9-2.4% in 2016.

Figure 3. Oil price contribution to the HICP excl. energy and food annual rates of change

Contribution of direct and indirect effect of oil price to Latvian HICP inflation

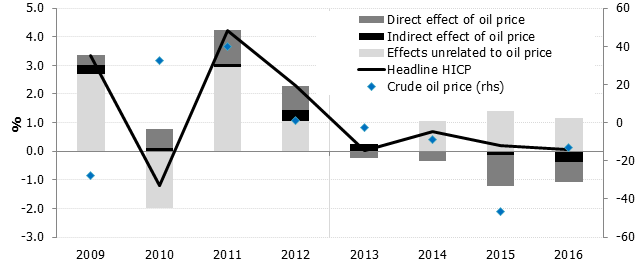

To find out to what extent changes in oil price have an impact on the HICP inflation in Latvia, we have estimated the impact of both effects (direct and indirect). Figure 4 confirms that in 2009-2016 the direct effect exceeded the indirect one and has had a faster impact on overall inflation.

Yet the indirect effect impacts overall inflation with a delay. For instance, the negative contribution of indirect effect rose from -0.1 percentage points in 2015 to -0.4 percentage pointsin 2016, while the negative contribution of direct effect declined. The greater importance of the indirect effect in 2016 is actually a delayed reflection of the events in the international oil market stemming from 2015.

Overall, our evaluation indicates that, if the price of oil had not experienced such a sharp drop in recent years, the HICP inflation in 2016 could have been at least 1.2%. The effect caused by the fast drop in the price of oil is one of the reasons why Latvian economists have erred in their recent inflation predictions, forecasting a faster price rises.

Figure 4. Annual rate of change in headline HICP inflation (%) and contributions of oil price effects (percentage points)

Future outlook

As we mention in this article, oil prices resumed climbing in 2016. If this trend will continue, the average price of oil in 2017 could reach 60 dollars, which would amount to about a 40% increase in the price of oil in year-on-year terms. It means that Latvian consumers will soon experience it in their expenses. The price of fuel is already rising and could be followed by heating tariffs and, finally, the prices of other goods and services.

Until now, inflation were likely to be overpredicted by Latvian economists along with dropping oil prices but as the trend changes in the oil market, the errors are likely to be in the opposite direction.

[1] We wrote about the direct effect of the price of oil and its impact at the end of 2015: https://www.makroekonomika.lv/kada-ir-naftas-cenu-tiesa-ietekme-uz-inflaciju-latvija

[2] A detailed description of the model can be found in our study: https://www.macroeconomics.lv/working-paper-cge-model-fiscal-sector-latvia

[3] See. ECB (2010). "Energy Markets and the Euro Area Macroeconomy" (See p. 75): http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbocp113.pdf?64f3b939c210c78e46eb1f1aa17e7044

[4] Data have been included in the model as differences in logarithm, but the unemployment rate and interest rate are in levels

[5] These two models also have the highest correlation, which means that they are better than the other models in describing the historical data trend.

Textual error

«… …»