The devil is in the detail – how to support the households and businesses hit by the crisis?

Almost a year has passed since the first COVID-19 case was registered in Latvia. This has been a challenging time as the virus and the related restrictions have affected almost each and every person and business in Latvia.

Although the scientists have been successful in developing effective vaccines, thus bringing some optimism for the future, the vaccine rollout is not as rapid as expected. Consequently, with high morbidity rates and hospital overload persisting, preventive measures to limit the virus spread seem to be inevitable also in the near future.

Nevertheless, each restriction, despite its relevance from the point of view of public health, causes economic consequences: lost jobs and income, closed businesses and huge stress in not knowing how to make both ends meet. Thus, financial support is an integral part of crisis management. In this respect, credit should be given to the government for having learned its lessons in spring, considerably expanding the range of support instruments in the second wave of the pandemic. Moreover, the announced amounts also seem to be quite substantial, i.e. up to 3.8 billion euro have been set aside for supporting the economy hit by the crisis. Despite that, the government has quite often been criticised for the lack of financial support.

With the financial support being close to 2000 euro per capita [1], how come people are still dissatisfied?

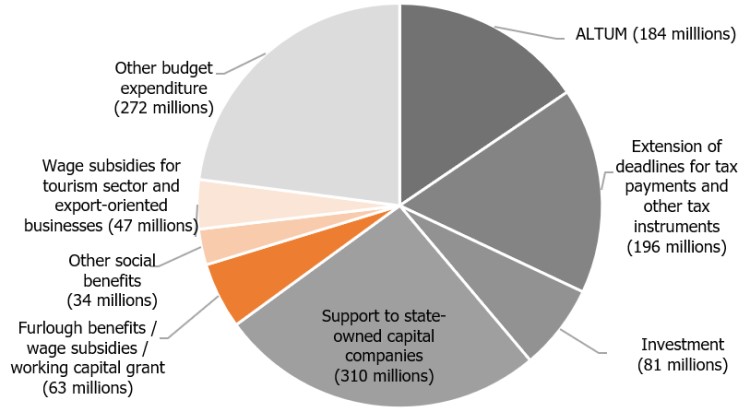

First, not all COVID-19-related financial support goes to the people directly affected by restrictions. Much of it is intended to increase funding for the healthcare sector (which is definitely necessary at the current stage), provide support to state-owned companies, provide credit guarantees, etc. The significance of the above measures should not be questioned; on the contrary, they are steps in the right direction. However, it is highly unlikely that these will help those which are hit the most by the virus and the related restrictions. Meanwhile, looking at the support instruments directly attributable to the above part of the society, i.e. furlough benefits, wage subsidies as well as financing to maintain the working capital flow – all to help retain the jobs for people to return to after the crisis – the amount allocated in the second wave of COVID-19 is considerably smaller, approximately 220 million euro [2].

Second, it is important to distinguish between the planned support and that which is actually paid out. Quite often the amount of the support paid is considerably smaller than that planned. Over the ten months of crisis last year, of the 3.8 billion euro planned for mitigating the COVID-19 impact, a mere 1.2 billion euro was actually allocated to stimulate the economy. Moreover, less than 153 million euro were given as grants (non-repayable) to compensate for income or as benefits [3]. A large share of the remaining financing was allocated for public procurement, inter alia for covering healthcare costs, for ALTUM guarantees and loans, as well as to support state-owned capital companies.

Chart. The public financing (in millions of euro) to mitigate the COVID-19 impact which had been actually paid out by 31 December 2020.

Meanwhile, under the new programmes for the second wave of COVID-19, 48.4 million euro or 22% of the available funding had been paid by 3 February in furlough benefits, wage subsidies and working capital subsidies (less than 26 euro per capita; in January, the average furlough benefit was 486 euro) [4].

One might ask – why does the support fail to reach the households and businesses hit most by the crisis?

There are several reasons for that. First, so far in the second wave of the pandemic, the economic downturn has been more moderate than in spring. On the one hand, this may reflect both the ability of many businesses to adapt to the new reality and the fact that in the second wave of the pandemic the industry and trade of goods remained quite robust globally. On the other hand, the fall in social mobility has not been so pronounced either in comparison with spring, probably on account of narrower/more targeted restrictions or because the public has grown weary of strictly complying with them.

At the end of 2020, the overall economy demonstrated considerably higher resilience to the challenges of the pandemic and the economic activity generally reported a smaller decline than initially expected; however, a number of sectors and businesses as well as their staff have been hit hard. Moreover, at the beginning of 2021, the drop in economic activity had already become more pronounced. Therefore, as long as the morbidity rates are uncomfortably high and the situation has not returned to normal, support instruments for people and businesses have a stable place in the government tool kit for addressing the consequences of the pandemic.

Second, the selection of the criteria for receiving support definitely plays a certain role. Pursuant to the Cabinet of Ministers Regulations [5], only those companies are eligible to apply for furlough benefits or wage subsidies whose income has decreased by at least 20% in comparison with their average income in the period from August to October 2020. So far, to receive working capital subsidies, a business had to meet the above criterion and, at the same time, it also had to demonstrate a turnover decline of at least 30% compared to the respective period of 2019. According to the recent addendums to the Regulation on working capital support approved by the Cabinet of Ministers, businesses with substantial turnover declines vis-à-vis 2019 will also be eligible for support, without having to demonstrate a 20% turnover decline compared to the turnover recorded for the summer months.

The qualification criterion of a 20% turnover decline vis-à-vis the average turnover over the period from August to October 2020 has a number of drawbacks. First, it disregards the fact that the pandemic affected businesses differently, and not all businesses were able to recover during the "calmer" summer months. Thus, for businesses that were kept in a state of emergency regime also during the summer period from August until October, it can be rather challenging to qualify for support. Second, when it comes to furlough benefits and wage subsidies, the criterion overlooks the seasonal turnover fluctuations across sectors. Therefore, businesses whose turnover tends to be larger in winter due to the nature of their activity may not qualify for support, even though their activity is currently significantly restricted. By contrast, businesses whose seasonal turnover is low during winter months, may have met the turnover decline criterion even without the impact of the pandemic.

In other words, under the existing regulation part of businesses most severely hit by the pandemic were denied the opportunity to receive support, whereas businesses that may not have been directly affected could qualify for furlough benefits and wage subsidies.

The good news is that such shortfalls can be easily remedied by ensuring that businesses with turnover declines vis-à-vis their pre-pandemic levels can also qualify for support. This means that the turnover should be compared with the respective month before the first wave of the pandemic, i.e. the respective month of 2019, without requesting businesses to demonstrate turnover declines vis-à-vis the levels recorded in August–October 2020. This would ensure that furlough benefits and wage subsidies would be available for employees of businesses which have seen their turnover shrink significantly due to the pandemic but have been unable to qualify for support under the existing regulation.

An equally important question: how long should the government continue to support businesses and households? The short answer: as long as high spread rates persist.

In a previous article, we already pointed out that we would hardly avoid a contraction in economic activity even without restrictions, as it would imply an uncontrolled spread of the virus and a substantial rise in the number of deaths. In such circumstances, people are unlikely to return to their usual lives, e.g. attend restaurants and cultural events. To some degree, this is confirmed by the analysis of the International Monetary Fund [6] suggesting that the contraction in economic activity observed in countries with tight restrictions does not differ substantially from that witnessed in countries with no restrictions and high numbers of cases.

It is worth restating the importance of the government support which should, as far as possible, prevent mass bankruptcies of the businesses severely hit by the pandemic.

Many heavily affected businesses operate in sectors with a relatively low value added, e.g. the hospitality sector; nevertheless, they play an important role in the overall economic ecosystem. It would be difficult to imagine Riga as the Baltic metropolis with high tourist flows and active international business and, at the same time, with underdeveloped hospitality infrastructure. Moreover, it would be naive to think that those employed in the hospitality and other services sectors would be able to easily and quickly find a job in sectors where labour demand is currently high, e.g. construction, manufacturing and IT. Thus, the liquidation of the above businesses would most likely result in higher unemployment and the concomitant side effects. There is also a risk that these workers would search for work and income abroad where the economy would have come out stronger on the other side of the pandemic, with the businesses of the respective sectors fully up and running again.

Moreover, the wave of bankruptcies would also be a major challenge for the institutions involved in insolvency proceedings, which can lead to sizeable erosion of accumulated capital with lasting negative repercussions on further performance of these sectors.

In conclusion, in light of the high uncertainty about the evolution of the pandemic, the related restrictions and decline in tourism and travel, vaccination challenges and the already weakened balance sheets of the businesses directly affected by the pandemic, support instruments should be available for a wide range of businesses and households which have been severely hit by the crisis.

Such support conditions will not only help prevent, to the extent possible, long-term economic scarring caused by the pandemic, but will also ensure a much more efficient response to the decline in economic activity and economic fluctuations caused by the virus spread in terms of the provided support levels.

[1] The figure was obtained by dividing 3.8 billion euro with Latvia's population (1.894 million according to the data of the Central Statistical Bureau (CSB) for January 2021).

[2] Additional programmes are also available for individual sectors, e.g. tourism.

[3] Additional subsidies have been also granted to farmers to stabilise their income.

[4] It should be noted that the increase was relatively rapid in January (9.1 million euro by 31 December 2020 compared to 48.4 million euro by 3 February 2021). Source: The Treasury and the State Revenue Service.

[5] Cabinet of Ministers Regulations No 709 on Furlough Benefits for Taxpayers to Ensure the Continuity of Their Economic Activity During the Crisis Caused by COVID-19 ("Noteikumi par atbalstu par dīkstāvi nodokļu maksātājiem to darbības turpināšanai Covid-19 izraisītās krīzes apstākļos"), Cabinet of Ministers Regulations No 675 Regarding the Provision of Aid to Taxpayers for the Continuation of their Activity in the Circumstances of the COVID-19 Crisis ("Noteikumi par atbalsta sniegšanu nodokļu maksātājiem to darbības turpināšanai Covid-19 krīzes apstākļos"), Cabinet of Ministers Regulations No 676 Regarding Aid to Undertakings Affected by the COVID-19 Crisis for Ensuring the Flow of Working Capital ("Noteikumi par atbalstu Covid-19 krīzes skartajiem uzņēmumiem apgrozāmo līdzekļu plūsmas nodrošināšanai").

Textual error

«… …»