What do demographic challenges mean to the Baltic labour market?

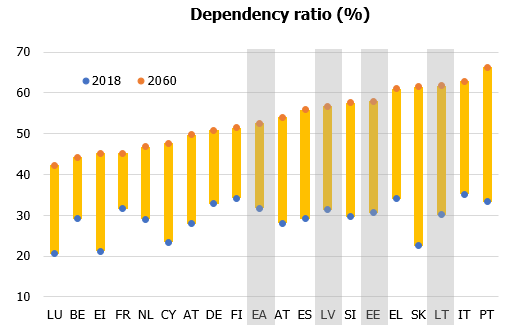

Currently there is one retirement age person per three working age inhabitants in Latvia and other Baltic countries. This ratio is expected to increase substantially in the near future.

If the current demographic trends persist, there will be less than two employees per each retirement age person as early as in 2060. The factors behind this trend are both the growth in retirement age population and the low fertility rates witnessed over the past few decades. As a result, the working age population is shrinking.

First, this trend will certainly pose a challenge to the fiscal policy, i.e. less taxpayers' money will be available to provide funding for pensions and benefits since the number of their recipients is increasing. This has been a subject of discussions repeatedly, including an article by my colleagues[1]. However, changes in the population demographic structure have significant effects on the potential of future economic growth as well. Participation of fewer people or less human resources in the creation of value certainly means constrained economic growth.

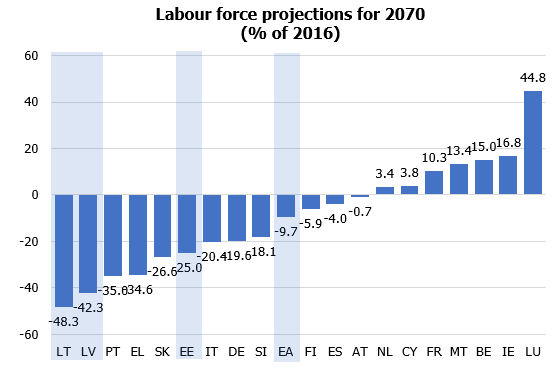

According to the European Commission's projections[2], labour force or working age population capable of generating income will decrease notably. Labour force is estimated to shrink in the Baltic countries due to the sharp fall in fertility rates in the 1990s, migration waves as well as the current low fertility rates. Lithuania and Latvia are projected to witness the fastest shrinkage of labour force among euro area countries. Working age population in Lithuania is expected to decrease almost by half or 48% by 2070 vis-à-vis the situation in 2016. Meanwhile, Latvia and Estonia are expected to see a 42% and 25% shrinkage of labour force respectively by 2070 compared to 2016.

Second, we will see the labour force not only shrinking but also aging. According to the International Monetary Fund's forecasts[3], retirement or pre-retirement age staff will be increasingly employed in the European labour market. Spain, Italy and Portugal are expected to witness the most rapid labour force ageing since currently approximately 14% of their employees have reached the pre-retirement or retirement age. As early as in 2035, this proportion is envisaged to expand from 24% in Portugal to 27% in Spain. Thus, almost every third employee will have reached the pre-retirement or retirement age by that time. This is related to both a rise in the average age of population caused by demographic trends and to the fact that a growing number of people of age 65 and above will seek to remain in the labour market and continue to work. This will be facilitated by the ongoing reforms of pension systems, by raising the retirement age and improving the quality of life, including that of medical services, enabling people to feel well and continue working despite ageing.

Quality instead of quantity

An ageing population, including also labour market changes, pose major challenges to economic policy makers. Economic growth and the potential of future growth are dampened by the decreasing number of people capable of engaging in generation of income. At the same time, the need for funding to cover expenses pertaining to pensions and benefits is becoming more acute.

One can try to hold back the expected shrinkage of labour force. It is clear, however, that the increase in fertility rates can no longer rapidly change the current demographic trends determined by the dynamics witnessed in the past. Another option is to encourage immigration, which can turn out to be an efficient short-term means for increasing the base of working age population. However, immigrant employees would not narrow the ratio between the retirement age and working age population since they would also age.

Another way of expanding the range of employees is to encourage people who could enter the labour market but do not so for some specific reason. This is, of course, a complex process involving not only the need to improve educational programmes to reduce the skill mismatch on the labour market but also the removal of other barriers preventing specific society groups from entering the labour market.

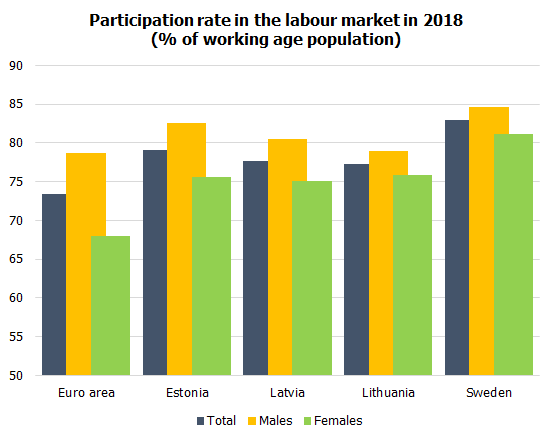

In its study on future demographic scenarios, the European Commission[4] acknowledges that if the participation rates of population in the labour markets across European countries reached the employment level currently observed in Sweden, the situation could change quite notably. 82% of the entire working age population are economically active in Sweden, including 81% of women are economically active. Meanwhile, 73% of working age population and 68% of women participate in the euro area labour market, i.e. nearly one in three women does not work and does not look for a job either. The percentage of people active in the Baltic labour market is relatively higher than the euro area average but still lower than that in Sweden. In the Latvian labour market, for instance, 77.3% of the entire working age population are active, but one in four women is not employed and does not seek employment either. Calculations by the European Commission suggest the following: if the participation of the euro area population in the labour market reached the level of Sweden, the number of economically active people participating in the labour market, generating and receiving income would increase by 21 million or 13%.

Such convergence would fully offset the downward trend in labour force projected in the euro area through to 2060. However, the situation varies widely across euro area countries. According to projections, labour force in the Baltic countries will shrink much faster than in Europe on average. Moreover, the rate of participation in the labour market is relatively high in the Baltic countries, thus the increase in participation in the labour market, reaching the Swedish level, would only partly offset the expected trend of labour force shortage. If the labour market participation rate in Latvia were raised to reach the Swedish level, additional 63 thousand economically active people would enter the labour market, expanding the labour force by almost 7%.

Provided we are aware of the fact that the shrinkage of labour force is inevitable, particularly in the Baltic countries as it arises on account of past events, and, furthermore, since the endeavours to find effective tools for halting the shrinkage of labour force have failed, we understand the need to think of ways of improving the quality of labour force and its ability to generating income or productivity. Of course, it is vital to improve the performance of the education and health areas as soon as possible. However, that is not enough. It is important to help people to adapt to the labour market, which has become more dynamic today, which requires an ability to develop and regularly acquire new knowledge, raise awareness about advanced technologies and find new solutions.

Development of the areas of general and higher education as well as research is certainly important with regard to the quality of labour force in the future. However, lifelong learning plays an increasingly significant role in the modern changing working environment, albeit only 6% of working age population aged over 25 take part in lifelong learning in Latvia and Lithuania. By contrast, Estonia has been systematically increasing access to various education opportunities[5] since 2006, when lifelong learning in Estonia was as rare as in Latvia, and one out of five Estonian inhabitants over the age of 25 continued to learn in 2018 which is the second highest indicator in the euro area after Finland.

Smaller but more capable labour force in the future

Each member of the public affects society and its capacity to develop. It is clear that the demographic trends prevailing over the past years have posed a major challenge for us, and the question arises who and how will live and work in Latvia in the coming decades. It is unrealistic to expect that the challenges having emerged over the past decades will resolve of their own accord. The number of working age population is following a downward path as a result of low fertility rates and migration flows. The potential of economic growth will be affected by fewer and fewer people ready to engage in income generation. Taking account of the fact that the population age structure will continue to change, and labour force resources will decrease, policy makers should focus on the development of the existing human resources. Concern for the population's health, skills and motivation to adapt and develop provides an opportunity to build smaller and more productive human capital. It would allow for society to continue developing and encourage - people to work here instead of leaving for another country.

_____________________________________________________

[1] https://www.makroekonomika.lv/cik-zali-dzivosim-vecumdienas-pensiju-sistemas-ilgtspejas-skietamiba

[2] Projections of demographic trends and their effects on the labour market are updated by the European Commission once every three years. The most recent report for 2018 is available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/ip065_en.pdf

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/demographic-scenarios-eu

[5] The Estonian Lifelong Learning Strategy adopted in 2014 sets objectives for 2020. The Strategy is available at https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/estonian_lifelong_strategy.pdf

Textual error

«… …»