Remote work – a forced experiment during the Covid-19 era or a lasting value?

Modern technologies enable us to organize company activities outside traditional offices and across national borders; however, remote work was rather uncommon before the Covid-19 crisis. The pandemic made many companies introduce rapid changes in their work organization, since it was working from home that allowed companies to continue their activities. At the same time, employees had an opportunity to work in healthier conditions and prevent Covid-19 from spreading in workplaces.

The pandemic as a catalyst of teleworking

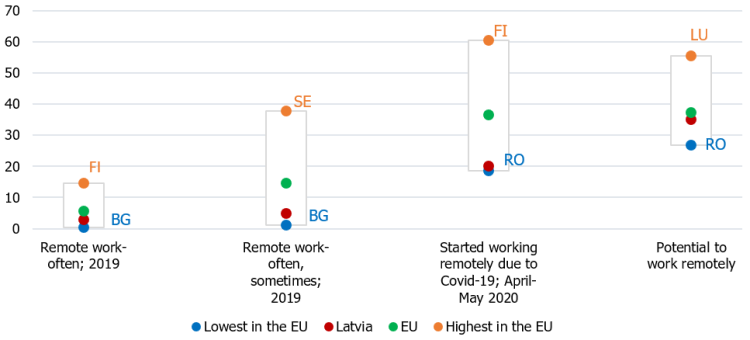

In 2019 (see Chart 1), the percentage of employees often working remotely was as follows: just about 5% of the employed in the European Union (EU), less in Latvia – 3%, while Finland topped the list with 15%. The beginning of the pandemic was marked by a rapid increase in teleworking, for example, 61% of employees worked from home in Finland, but in the EU – on average 37% of the working population. Thus, during the initial stage of the pandemic, practically all employees, whose jobs according to their job descriptions were assessed as technically teleworkable jobs [1], started working from home.

Chart 1. Remote work in the EU in 2019 and in April–May 2020, estimate (% of the employed).

Remote work increases productivity under normal circumstances

Teleworking has already been mentioned in relation to the oil crisis and the skyrocketing fuel prices witnessed in the 1970s, making people think [2] about the benefits brought by the reduction of transport costs when working from home.

The impact of remote work on productivity was also studied before the pandemic, and it mostly helps boost productivity under normal circumstances [3] [4] [5]. It is directly attributable to a higher satisfaction of the labour force due to reconciliation of work and private life, saved time and money as well as, for many, also greater autonomy over the organization of their work.

Productivity also increases indirectly through reduced company costs for office premises and equipment, thus allowing businesses to use their resources for more productive investment. This also offers opportunities for hiring employees with higher qualifications who are otherwise restricted by the connection to their place of residence.

Meanwhile, at the society level, benefits brought by productivity growth improve the population's well-being. They also include reduced traffic jams and pollution, less use of paper and plastic materials and a possibility to revive rural areas.

Risks associated with remote work that intensified during the crisis may also persist in the post-crisis era, i.e. longer working hours, fewer breaks and social isolation accompanied by reduced communication and information flow. However, it is possible to eliminate these risks by allowing employees to make a free choice between teleworking and mixed working time in the office and at home.

During the pandemic, remote work is often the only possibility therefore the above risks have aggravated. Moreover, productivity decreases on account of the negative impact of the pandemic on other areas. For example, remote school classes make parents focus on teaching their children, while closed kindergartens – pay particular attention to looking after their children. Limited chances of having entertainment outside the home enhance social exclusion. The necessity to switch immediately to working from home has resulted in inappropriate working conditions and IT solutions. People also lack experience of teleworking since remote work was not a widely adopted practice before. Living conditions are also important for efficient teleworking, especially during the pandemic when the entire family is often at home. This is a lasting risk for Latvia since estimate [6] shows that 42% of the population live in overcrowded households [7], where it is difficult to find a secluded space and work efficiently.

Teleworking helps to strike a balance between work and family life; it contributes to social security during the Covid-19 crisis

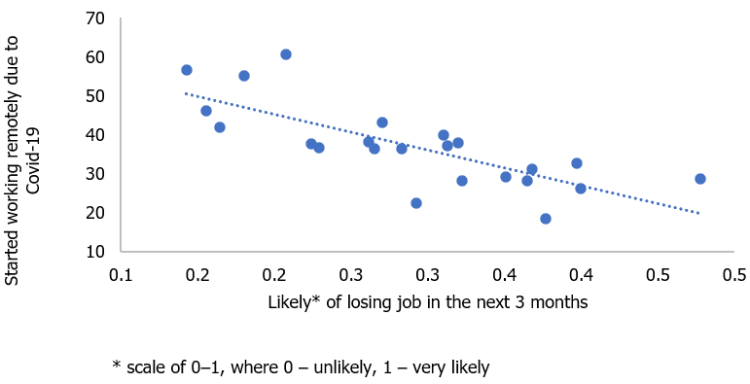

Under normal circumstances, remote work enhances employees' social satisfaction with the balance between work and private life. Although remote work can lead to a productivity decrease during the pandemic, teleworking, in addition to the most important positive aspect – a safer environment for human health – also highlights a social security aspect involving the assessment of employment retention (see Chart 2).

Chart 2. Remote work and self-assessment of job loss possibilities in the EU (% of respondents).

Teleworking possibilities differ from country to country

Both the assessment of teleworkability and adaption to remote work organization during the pandemic varies across countries. One of the reasons for this is differences in the sectoral composition of the economy and profession groups.

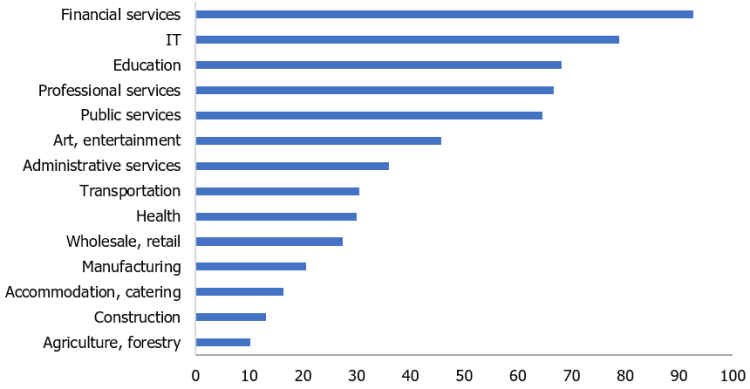

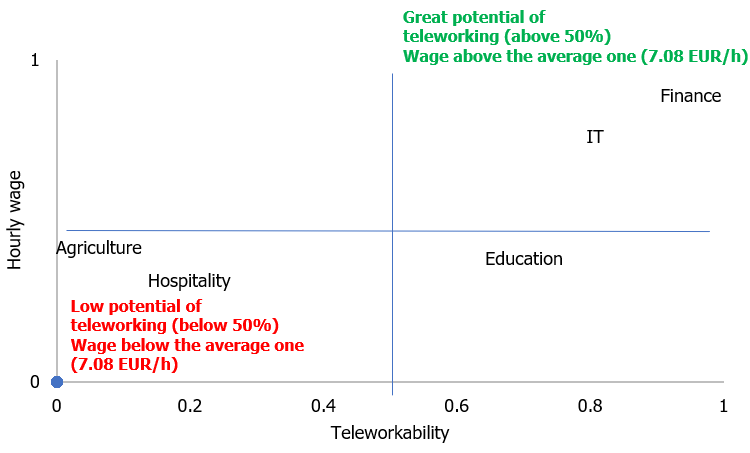

It is easier to introduce teleworking if services sectors, having no face-to-face interaction with customers, prevail in the economic structure. Researchers have assessed that employees of the financial and information technologies (IT) sectors are best placed to work remotely (see Chart 3), while the physical presence of those employed in the agricultural or construction sector is required. The presence of employees is also highly needed in the services sectors like hospitality or retail trade, although these sectors are gradually introducing tools substituting people.

Chart 3. Teleworkability in the EU (% of those employed in the economic sectors).

Cross-country differences also exist within sectors, for example, in terms of the number of managers and employees having higher qualifications (who often have more possibilities to adapt to remote work) and in terms of the management style and work organization. Teleworking is impossible in professions where job tasks cannot be performed without the physical presence of employees (e.g. nurses, production line or agricultural workers) or where technologies that allow teleworking are not available yet.

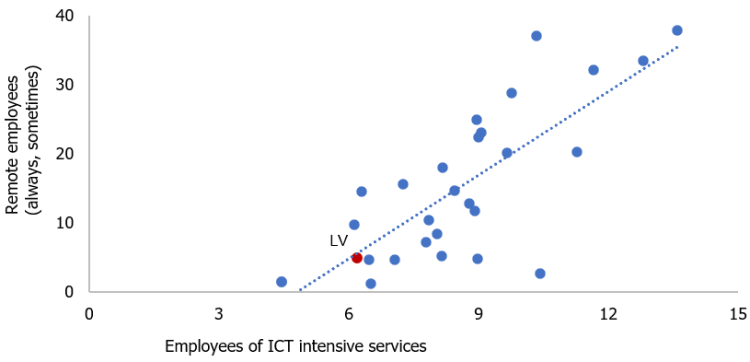

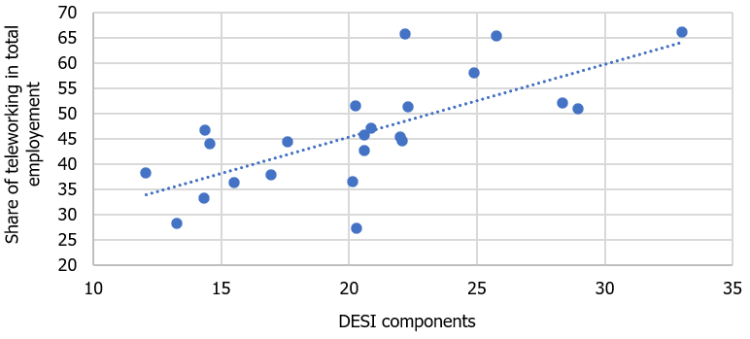

Looking into more detail, if the economy is characterised by advanced information and communication technologies (ICT) intensive industries, remote work is more widespread not only in these industries but also in other areas due to extensive availability of technological solutions (see Chart 4).

Chart 4. Remote employees and those employed in ICT intensive industries in the EU in 2019 (% of the employed).

Another reason why opportunities of remote work vary across countries is the size of companies, since larger businesses better adapt to teleworking than smaller ones. Also, the self-employed are usually more adapted to working from home.

Remote work is not available for everybody – it increases inequality during the Covid-19 crisis

Researchers have assessed the teleworkability of countries and industries , and it is obvious that not everybody can benefit from it. Industries with higher salaries and professions involving higher qualifications offer better possibilities of teleworking. Thus, the groups of employees who receive lower wages become more vulnerable during the Covid-19 crisis, and the inequality observed before it might increase. Therefore, also from the perspective of teleworking opportunities, it is important to target the state support, available during the pandemic, at vulnerable people hit by the crisis.

Also in Latvia, the industries offering greater opportunities of teleworking – the sectors of financial services, IT and professional services – (e.g. legal and accounting services) report considerably higher remuneration than the national average (1.1 – 1.9 times higher). Meanwhile, the agricultural, construction and hospitality sectors, where possibilities of teleworking are limited, report lower wages than the average in the country.

The education sector is an exception in Latvia. It offers great opportunities of remote work that are widely used during the pandemic (at the same time, intense discussions about returning to classroom education are ongoing, and such return is practised whenever possible); however, wages of teachers are significantly below the country average (see Chart 5).

Also, when looking at professions, remuneration of the managers (more than 70%), whose duties can technically be performed remotely [8], is above the country average (11.60 EUR per hour in 2019). Meanwhile, wages of elementary workers requiring their physical presence in the workplace are low (4.43 EUR per hour), and estimates show that about 3% of the employed can potentially use the opportunities offered by teleworking. It is yet another evidence of the fact that the employees receiving lower wages are subject to a higher risk during the pandemic.

Chart 5. Regular gross wage per hour worked (EUR) in Latvia and teleworkability (% of the employed) by industries according to NACE.

Social interaction and weak IT skills pose obstacles to remote work

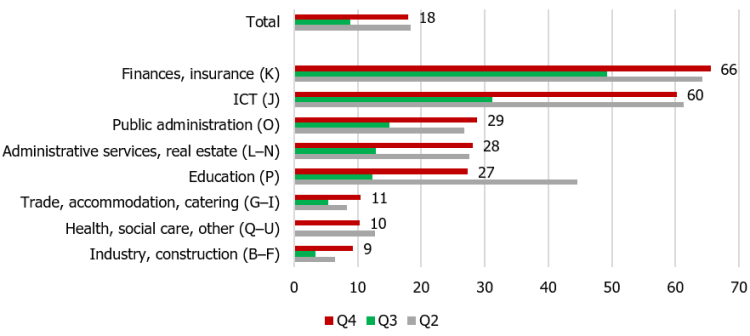

The potential opportunities of teleworking are not always fully exploited (also during the Covid-19 crisis). According to job specifics, 35% of the employed in Latvia [9] could technically work from home. However, only about 18% (CSB) or just a half of them used this opportunity during the pandemic outbreaks. Three quarters of the employed working in the financial services and IT sectors, where Latvia had the largest share of remote employees (above 60%), did not use the opportunity of working from home either.

Researchers [10] consider that in two thirds of professions, where teleworking is technically possible, social interaction has to play a crucial part. Thus, 37% of the employed in the EU can work remotely; however, only 13% of employees do not need social interaction. For example, social interaction is necessary for the professions like managers or teachers who can technically perform their duties remotely. Of course, during outbreaks of the pandemic, members of these professions also work remotely as evidenced by the data showing that, on average, almost all teleworkable employees in the EU have started working from home.

This suggests that remote work will still be more widespread after the pandemic than before it, but it will decline overall. This was well demonstrated by changes in the share of employees working remotely in Latvia in 2020 (see Chart 6). The number and share of remote employees hiked rapidly during the pandemic outbreaks, but decreased during the summer period when the spread of Covid-19 abated and the economic activity recovered. The second wave of the pandemic has also made people to return to remote work, which is safer for human health.

Chart 6. Remote employees in Latvia in Q2–Q4.

For remote work to be efficient, it is necessary to have an appropriate IT infrastructure, skills and managerial ability to switch to such work organisation. IT skills and involvement of companies in enhancing these skills are the objective factors behind differences between countries concerning company abilities to adapt to teleworking. Countries, where people and businesses are better prepared for using IT solutions, reported a larger share of remote employees during the pandemic (see Chart 7).

Chart 7. Components of the Digital Economy and Society Index (digital skills of human capital and the integration of digital technology by companies) in the EU in 2020 and the employed who worked from home on a daily basis before the pandemic and who started working remotely in the EU during the pandemic (% of the employed).

Latvia ranked 18th among the EU countries in the total Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) [11] in 2020. Meanwhile, with regard to the components describing preparedness of the population and businesses to apply IT solutions, i.e. digital skills of human capital and the integration of digital technology by companies, Latvia is among the poorest performing countries, with only Bulgaria, Romania and Greece reporting weaker results.

Economic and social benefits show that it is desirable to adopt a wider teleworking practice than before the crisis

Under normal circumstances, remote work increases productivity and helps people to strike a better balance between their work and family life. Businesses, society and environment all benefit from it. Thus, more widespread teleworking would be preferable also after the pandemic.

In Latvia, the legal framework governing remote work (amendments to the Labour Protection Law) was already discussed and defined before the pandemic, but became effective on 1 July 2020. It can serve as a potential catalyst of teleworking. During the pandemic, governments of some countries encouraged a broader availability of remote work (e.g. in Italy via informative support, in Japan through financial support). Latvia has not envisaged any support directly targeted at encouraging remote work, except for tax exemptions for employees' expenses related to teleworking [12] if the employer covers such expenses.

The experience of 2020 showed that remote work will be more common after the pandemic than before it. It is a positive development since it can boost productivity, especially if the balance and choice between remote and in-office work is preserved.

Digital skills are essential prerequisites for working remotely in potentially teleworkable industries and professions and for offering such opportunities to employees. Improvement of digital skills has already been highlighted in the context of the breakthrough of economic modernization and growth. Nevertheless, the role of digitization should be re-emphasized also in the context of teleworking to improve well-being of individuals and society. Physical investment and improvement of skills, including boosting capacity of the use of managers' digital potential require funds. Funding for digitization is available under the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility and it should be earmarked and used for strengthening the economic potential.

References

[1] Hereinafter, assessments of teleworkability in countries and sectors made by Milasi et al, 2020 (EC) have been used; similar assessments have been made by, e.g. Bates, Vivian, 2020 (ECB), Dingel, Neiman, 2020 (NBER), Berg, Bonnet, Soare.

[2] In 1973, Jack Nilles, a former NASA communication systems engineer, started to use electronics in teleworking.

[3] N. Bloom, J. Liang, J. Roberts and Z. Jenny Ying, "Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment", London, 2013.

[4] E. G. Dutcher, "The Effects of Telecommuting on Productivity: An Experimental Examination. The Role of Dull and Creative Tasks", Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2012.

[5] OECD, "Productivity gains from teleworking in the post COVID-19 era : How can public policies make it happen?", 2020.

[6] Eurostat.

[7] A household is considered overcrowded if it does not have the minimum number of rooms depending on gender, age and relationship of household members (according to Eurostat definition).

[8] ILO, "Working from Home: Estimating the worldwide potential", Policy brief, Switzerland, April 2020.

[9] S. Milasi, J. Hurley, M. Bisello, I. González-Vázquez and E. Fernández-Macías, "Who can telework today? The teleworkability of occupations in the EU", European Commission, 2020.

[10] M. Sostero, S. Milasi, J. Hurley, E. Fernández-Macías and M. Bisello, "Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: a new digital divide?" JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology, 2020/05.

[11] The indicator published by the EC sums up digital performance of countries and describes digital competitiveness.

[12] The law "On Personal Income Tax" provides for the tax exemption in the 2021 tax year for the expenses incurred by an employee while teleworking and covered by the employer if the total amount does not exceed 30 euro per month.

Textual error

«… …»