Youth unemployment: a real problem or tyranny of numbers?

This year the International Children's Day (1 June) was marred by media headlines dedicated to soaring youth unemployment rates almost everywhere in the world. However, the situation with the youngsters' position in the labour market is much less clear than it seems at first glance. What lies behind the dismal unemployment numbers?

Two useful figures for the politicians' portfolio

The dismal unemployment headlines rely on two figures that form a common base for the youth unemployment debate.

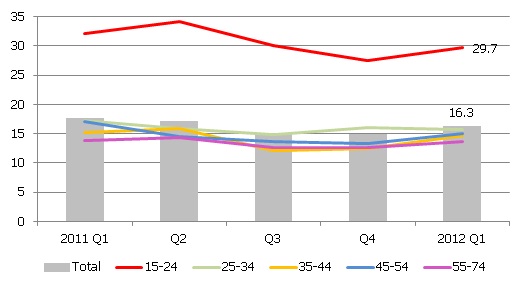

First, the job seekers' rate among youngsters in Latvia (30%) is twice as big as among other age groups (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Job seekers' rate in Latvia by age group (% of economically active population)

Source: CSB data

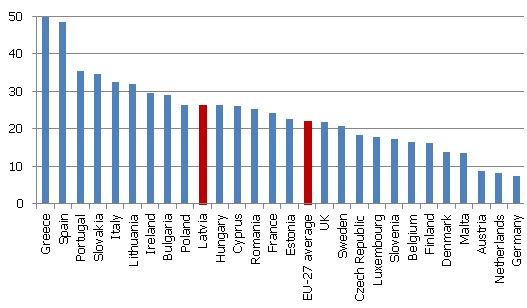

Second, a similar story applies to other EU countries as well. On the one side, Greece and Spain are leaders with a 50% youth unemployment rate (see Figure 2), leading to breaking-news headlines "every second youngster without a job". The budget deficits in these countries ranked the second and the third biggest in the EU in 2011 (9.1% and 8.5% of GDP respectively), but that did not help to prevent a rise in unemployment. It is another illustration of how a "socially responsible" policy (which in reality is irresponsible as the public spending keeps exceeding revenues forever) may soften the consequences of a crisis. On the other side, there are three countries where the youth unemployment is below 10% - Germany, Austria and Netherlands - we will see the sources of their "miracle" shortly afterwards.

Figure 2. Job seekers' rate among youngsters (age group of 1524 years) in Q4 2011 (% of economically active population)

Source: Eurostat data

Normally these two figures are the only ones in the politicians' portfolio regarding youth unemployment, followed by emotional speeches on "the lost generation", etc. Sadly, the EC president Barroso also referred to Figure 2 when sending a letter to seven EU countries (also Latvia) with the highest youth unemployment rates, calling for action to solve the problem.

However, in reality unemployment is no more widespread among youngsters than among other age groups (see Table 1).

Table 1. Participation of Latvia's youngsters (aged 15-24) in the labour market in Q1 2012, in thousands

| Total number of young people |

255 |

| Inactive (pupils and students) |

155 |

| Economically active (employed or looking for work) |

100 |

|

of which: employed |

70 |

|

job seekers |

30 |

Source: CSB data

The ratio of job seekers to economically active youngsters is the dismally famous 30% unemployment rate. I wonder, however, whether due to 30 thousand youngsters seeking a job (of which only 15 thousand are registered with the Latvia's State Employment Agency – NVA), the misery label could be attached to all 255 thousand Latvian youngsters.

What is better for a youngster – education or work?

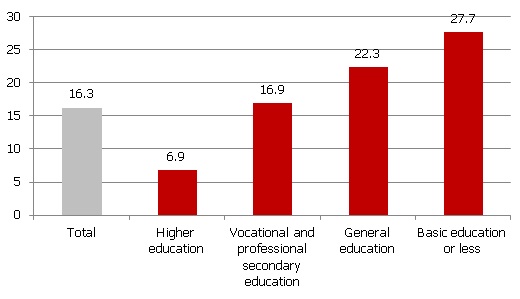

Quite often we hear (mainly from low-skilled labour employers) innocent calls to integrate 155 thousand pupils and students into the labour market since "everybody is studying useless things while we have a labour shortage". If studies really were useless, we would see similarly high unemployment rates among educated and less-educated people. In reality, however, education does improve performance in the labour market by significantly reducing unemployment risk (see Figure 3). So I would disagree with the opinion that authorities should somehow stimulate Latvian pupils and students to enter the labour market at the expense of studies.

Figure 3. Job seekers' rate by education level in Latvia (Q1 2012; % of economically active population)

Source: CSB data

Let's look at a hypothetical example. If only 1% of youngsters were studying, the remaining 99% would be rather successful in the labour market. First, if the majority of population would be uneducated, being low-educated would not be a disastrous signal to the employer. Second, many capable and talented young people would obviously be among the 99%. Conversely, if 99% youngsters were studying, the remaining 1% would definitely be out of work since employers would be free to hire educated workers.

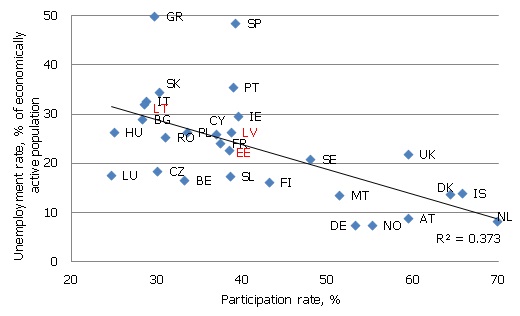

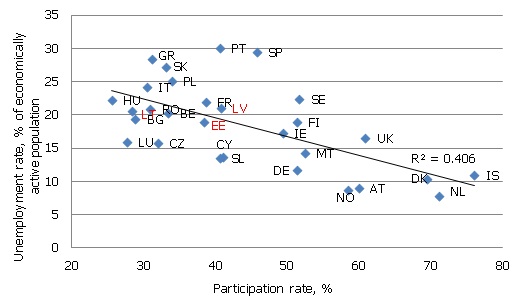

In the EU context, this example could explain "the miracle" of the Netherlands, and partly also the low youth unemployment rates in Germany and Austria. For instance, if Latvia had a similarly high economic activity rate as the Netherlands do, the youth unemployment rate would not exceed 10% either (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Youth participation and unemployment rates in Q4 2011

Source: Author's estimation based on Eurostat data

The relation between the youth participation and unemployment rates is even stronger in the longer term (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Youth participation and unemployment rates, Q1 2005 – Q4 2011, averages

Source: Author's estimation based on Eurostat data

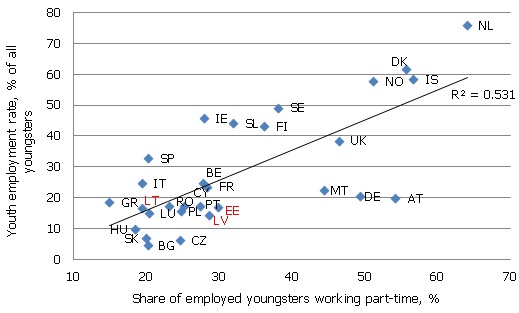

Moreover, in some countries (e.g., the Netherlands) it is common for youngsters to work part-time so they can continue studies after entering the labour market. Unsurprisingly, the youth employment rate in these countries is higher than in Latvia where the society is not accustomed to a flexible job schedule, thus many youngsters have to choose between studies and a full-time job (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Youth employment rate and the share of youngsters working part-time in Q4 2011

Source: Author's estimation based on Eurostat data

So we may conclude that "the youth unemployment problem" is not a problem per se in Latvia. It is simply a combination of low skilled unemployment and regional unemployment problems. Youngsters suffer from these problems just like people in other age groups do.

Causes of youth unemployment do not lie in youngsters

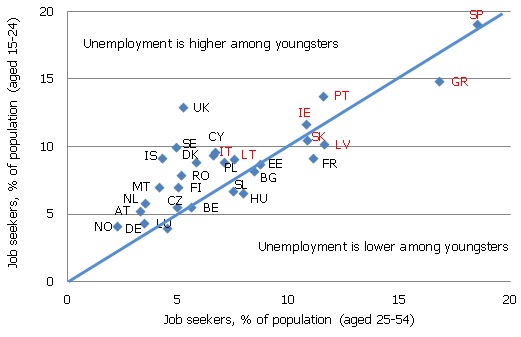

A quick way to identify countries where "youth unemployment" is a problem per se (i.e., countries where its causes lie in youngsters themselves) is to compare the youth unemployment with the respective indicator in other age groups by dividing the unemployed by total (rather than by the economically active) population. The eight countries that have received Barroso's letter calling for action to combat youth unemployment are red-coloured in Figure 7. Like in Latvia, in most of these countries the causes of youth unemployment do not lie in youngsters. If one still asked me to name a country where youth unemployment should be combated in particular, it would be the UK. It is the UK where the youth unemployment is not only higher than in Latvia but also 2.5 times higher than in other age groups in the UK.

Figure 7. Unemployment in selected age groups, % of population

Source: Author's estimation based on Eurostat data

Redistribution of EU funds to combat the youth unemployment could still be beneficial if these measures improve education and/or skills of young people (rather than result in employing one group of youngsters to excavate a trench and another group to fill up the trench in order to obtain a short-term improvement in youth unemployment figures). New job places for youngsters should not be low-skilled since such would only demotivate them from developing their professional skills, thus increasing the number of social benefit recipients in the future (see Figure 3). Moreover, many practical skills (for real life, not only for grade) should be obtained at school. It may look funny if after 12 years at school a young person needs computer proficiency, foreign language and CV writing courses in order to enter the labour market.

This Article was published by Delfi on June 5, 2012

Textual error

«… …»