Labour Market Reforms in the European Union: an Overview

Labour market policies (LMPs) are a complex set of rules established with the aim to ensure balance between labour market demand and supply.

They should also support employees in times of unfavourable economic conditions by providing social protection in the form of unemployment benefits and active labour market policies (ALMPs) developed to improve skills as well as ensure fair wages and adequate working conditions. At the same time, employment protection legislation (EPL) should provide for sufficiently flexible LMPs to allow employers to adjust wages and employment when facing adverse economic shocks. Overly protective EPL prevents firms from adjusting their labour costs resulting in a higher rate of default, prolonged economic recovery and an even higher rate of unemployment.

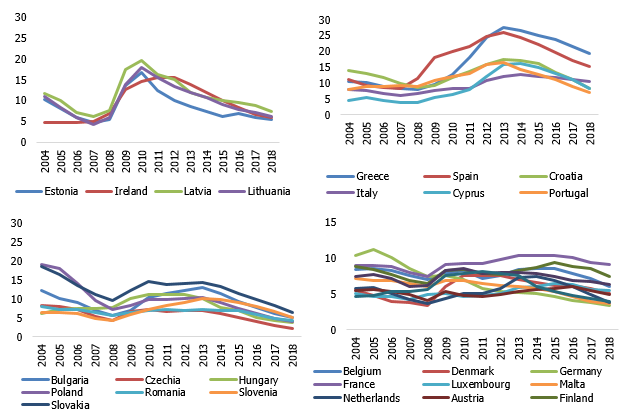

Prior to the crisis of 2008, labour market policies as regards wage-setting, active labour market policies and the EPL were quite heterogenous in the European Union (EU). At the same time, the prevalence of labour market institutions, such as unionisation and collective agreements, differed significantly (see European Commission (2014)). This, together with the various levels of economic disbalances, such as economic overheating and housing price bubbles, determined the depth and length of the unemployment adjustment in each of the EU countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The unemployed; % of the active population

In response to the economic downturn, policy makers introduced various LMP changes, e.g. amendments to legislation on employment protection, wage-setting and labour taxation, thereby helping firms to adapt to new economic realities. At the same time, these reforms provided extra social support to the unemployed and facilitated faster labour market recovery by providing new ALMPs to enhance the skills and employability of those without a job.

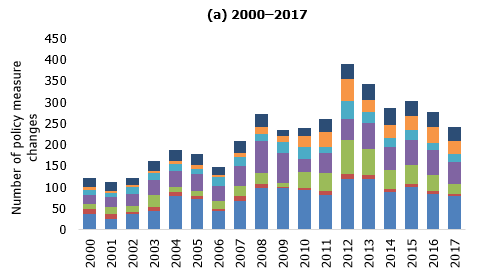

Since the initial LMPs differed among countries, the implemented labour market reforms also varied both in terms of their structure and volume. The number of amendments to labour market legislation has doubled since 2007, with most amendments (389) introduced in 2012. Portugal, Belgium, Greece, Spain and Italy implemented more than 100 policy measures in 2008–2013 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of changes in labour market policy measures in EU countries

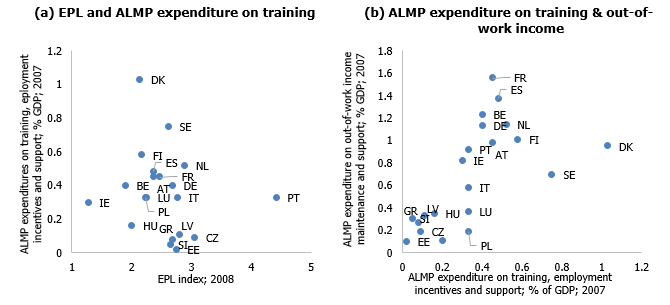

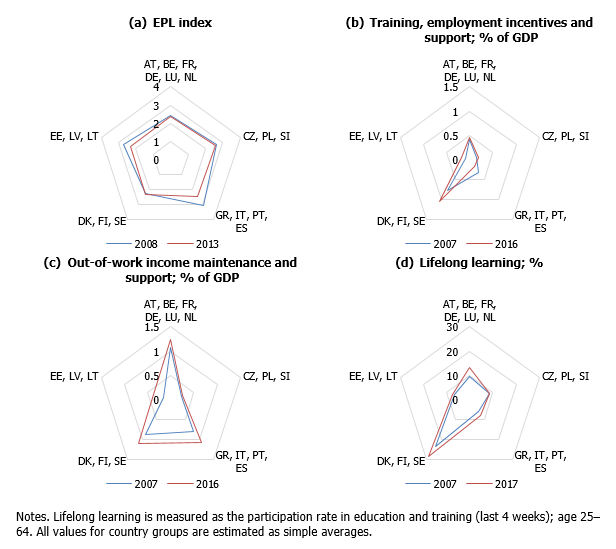

Prior to the crisis, the strictness of the EPL, ALMP expenditure and unemployment support measures differed substantially among countries (see Figure 3). While stricter EPL ensures employment stability for workers, it can also discourage employers from hiring new workers and limit their options for labour cost adjustment. In 2008, Portugal, Greece, Italy and Estonia were among countries with the highest EPL indices, whereas the Eastern European countries and Greece had the lowest level of ALMP expenditure and unemployment support. Hence, with unemployment rising, these countries faced higher social pressures.

In the Southern EU countries, i.e. Greece, Portugal and Spain, the disappointing labour market outcomes intensified during the EU sovereign debt crisis of 2010–2013 (see Figure 1). To make labour markets more efficient, these countries had to implement the most extensive labour market reforms covering wage-setting policies, policies promoting the reallocation of labour to more productive jobs/sectors or temporary reduction of working hours as well as policies extending the safety net for the unemployed.

The Baltic States, i.e. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, experienced significant increases in unemployment during the early stages of the global financial crisis in 2008–2009. Due to the low level of unionisation and the low share of collective agreements, as well as the significant growth of wages prior to the crisis, employers were able to adjust wages and employment downwards, thereby regaining price competitiveness (see Izquierdo et al. (2017), Fadejeva and Krasnopjorovs (2015)). In 2009, unemployment increased sharply, thus, labour market changes were mostly focused on providing a safety net for the vulnerable, reforming the ALMPs and reducing the tax burden to boost the economy. Estonia also relaxed the EPL measures significantly.

In the rest of the EU, unemployment changed moderately, and labour market reforms were driven primarily by the objective of making it easier for firms to attract skilled workers and to adjust to fast-changing markets (via adequate employment protection legislation), while providing the necessary security to employees (European Commission (2017)).

Figure 3. EPL and labour market policies before the crisis

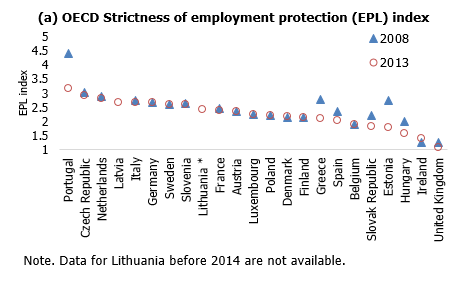

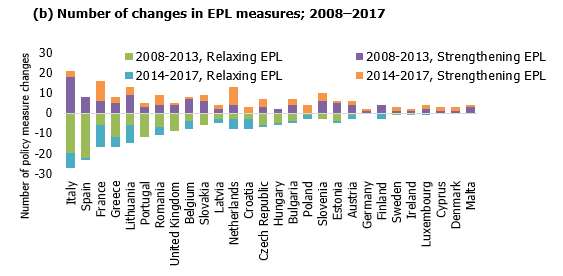

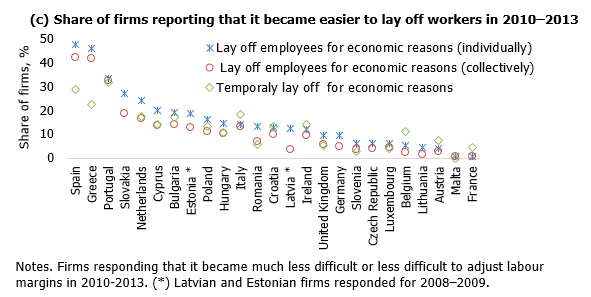

Despite quite a large number of job protection legislation reforms, the OECD EPL index remained unchanged in most EU countries in 2008–2013 (see Figure 4, subplot (a)). This can be explained by the different nature of implemented policies, some of which are enhancing the employment protection flexibility and some are strengthening it (see Figure 4, subplot (b)). In Portugal, Greece and Spain, the majority of employment protection reforms were flexibility-enhancing resulting in a decline of the EPL index. In Italy and France, on the other hand, legislation amendments took various directions, with the EPL index remaining unchanged. The effect of the employment protection reforms, as perceived by firms, is consistent with the development of the EPL index (see Figure 4, subplot (c)). Around 40% of the Spanish and Greek firms participating in the ECB's Wage Dynamic Network Survey reported that laying off workers due to economic reasons became easier in 2010–2013. In Italy and France, this share was approximately 20% and 5% respectively. Estonia, Hungary and Slovakia also relaxed their EPL-related measures (see Figure 3, subplot (a)) making it easier for firms to lay off their workers (see Figure 4, subplot (c)).

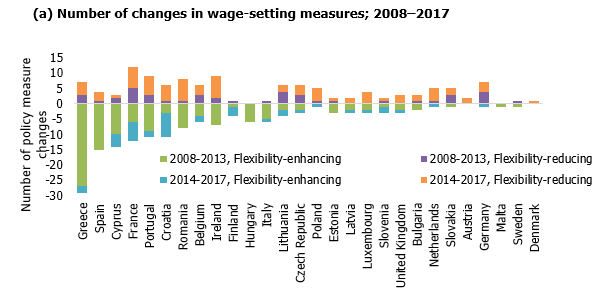

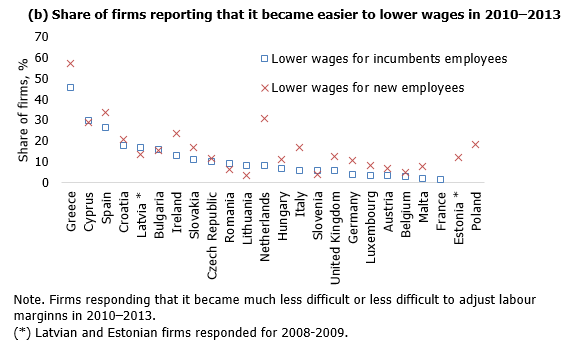

In 2008–2013, Greece, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus introduced the largest number of reforms enhancing their wage-setting flexibility (see Figure 5, subplot (a)). Labour market reforms in these countries modified some of the most important institutional aspects of the labour market, such as the degree of centralisation of the collective bargaining system. It is therefore not surprising that over 30% of firms in these countries reported that it became easier to adjust or lower wages in 2010–2013 (see Figure 5, subplot (b)).

It is important to note that the ease at which employers are able to lower wages can be explained by several factors. It can reflect a pure effect of legislative amendments or behavioural changes of individuals due to adverse economic conditions. The results of the Wage Dynamics Network (WDN) Survey show that employment was mostly affected by legislative amendments; however, wage reduction was possible due to a combination of both legislative and behavioural effects (see Izquierdo et al. (2017), Table 12). Thus, even in countries with already flexible wage-setting, such as Eastern European countries and Ireland, approximately 20% of firms reported that the lowering of wages had become easier (see Figure 5, subplot (b)). Adjusting the wages of new hires seems to have become less difficult in all countries.

Figure 4. EPL reforms and change in the ease of laying off employees

Figure 5. Wage-setting reforms and change in the ease of lowering wages

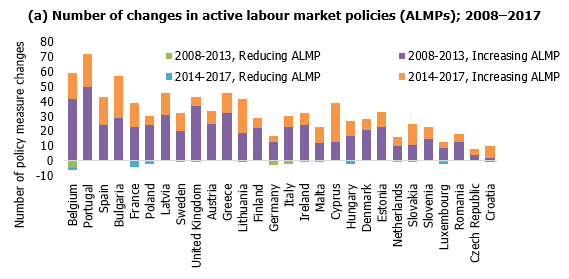

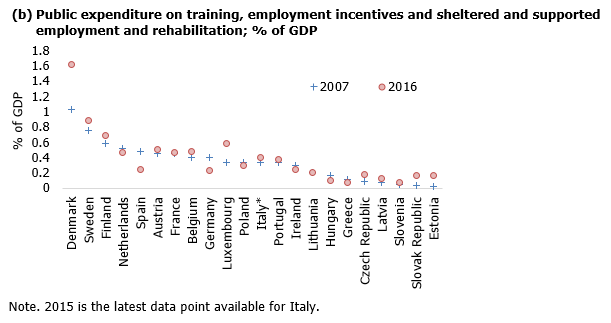

From the policy perspective, it is important to combine increased labour market flexibility with ALMPs to allow workers to be redeployed quickly to new sectors and use new job opportunities. Even before the crisis, the share of new ALMP measures introduced to labour market policies was growing (see Figure 2, subplot(a)). Since the crisis, the importance of the AMPL measures has increased (see Figure 6, subplot (a)). The share of public expenditure on training, employment incentives and sheltered and supported employment and rehabilitation increased in the majority of the EU countries (% of GDP; see Figure 6, subplot(b)). Scandinavian countries are leaders in this respect.

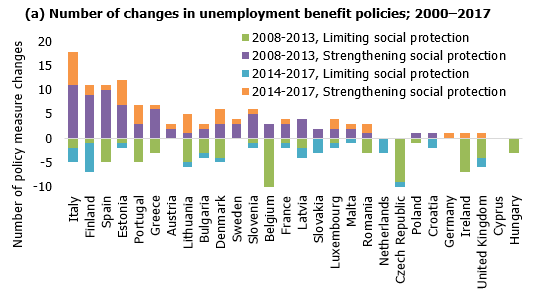

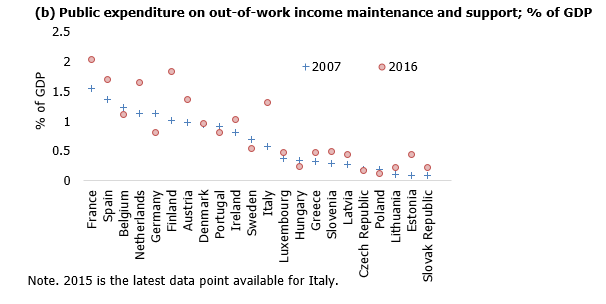

In parallel with improving the ALMP measures, many countries also had to adjust their unemployment benefit policies. Unemployment benefits serve a dual purpose: they provide direct support for those who suffer a loss of income during a period of unemployment (which also serves as an automatic financial stabiliser for the economy as a whole), and they help maintain the individual's continuing employability thus supporting their re-employment efforts (European Commission (2014)).

Figure 6. Change in the number of active labour market measures and public expenditure

In Italy, Spain, Finland and Estonia, social protection was mostly strengthened by the changes in unemployment benefit policies (see Figure 7, subplot (a)) resulting in higher public expenditure on out-of-work income maintenance and support even eight years after the crisis (% of GDP; see Figure 7, subplot (b)). Belgium, the Czech Republic, Ireland and the United Kingdom, on the other hand, implemented several measures to improve the job-seeking efforts of the unemployed, for example by increasing degressivity of unemployment measures, activating monitoring and raising the level of requirements.

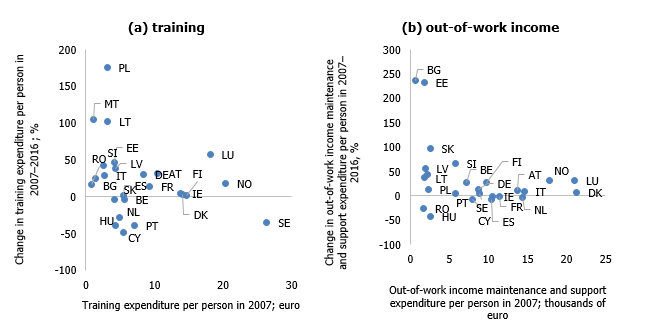

The growth of unemployment-related expenditure per person illuminates a different aspect of adjustment. Per person expenditure on labour market activation or out-of-work support mostly grew in countries with previously lower expenditure levels (see Figure 8). Since 2007, per person expenditure on training has increased by more than 100% in Poland, Malta and Lithuania and by approximately 50% in Slovenia, Estonia, Latvia and Luxembourg. Meanwhile, per person expenditure on out-of-work support increased by 200% in Bulgaria and Estonia and by more than 50% in Latvia, Slovenia and Slovakia.

Figure 7. Change in unemployment measures and public expenditure on out-of-work income maintenance and support

Figure 8. Change in public expenditure on out-of-work income and support and training per person; %; 2007–2016

Figure 9. Change in labour market institutions

To sum up, labour market policies are a complex set of measures targeting capacity to resist shocks and quickly recover from them. This is, however, particularly challenging given that an effective relationship between employment protection measures, labour market activation measures, and systems of social support is difficult to achieve (European Commission (2014)). Differences in labour market institutions and initial levels of support determined the direction of the LMP reforms. Greece, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus achieved higher levels of employment and wage flexibility. Meanwhile, most Eastern European countries increased their per person expenditure on active labour market programs and unemployment support. Estonia improved all three. The overall result shows, however, that despite improvements in almost all measures, the support for lifelong learning, unemployment benefits and active labour market policies in Eastern and Southern European countries is still lagging behind their Western and Northern neighbours (see Figure 9).

Current LMP discussions

Despite higher flexibility and therefore better risk-resistance of the current European LMP structure, there are several concerns in the policy discussions related to change in the work arrangements and digitalisation. Among others, the adverse effects of social protection segmentation (see European Commission (2018a)), i.e. the division of the labour market in secure and insecure jobs depending on the type of employment contract. This gap has widened with the expansion of non‐standard forms of employment since the crisis. Such developments, e.g. a rise in the number of the employed subject to the micro-enterprise taxation regime, are also observed in Latvia.

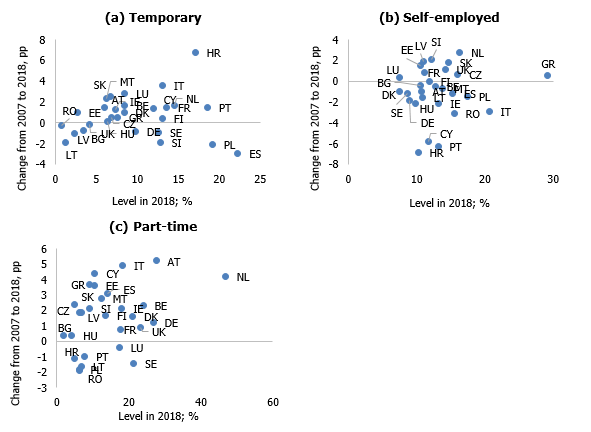

The popularity of different working arrangements varies across EU countries (see Figure 10), e.g. the share of temporary workers in the total number of the employed in Poland, Spain and Portugal is approximately 20%, whereas that in the Baltic States, Romania and Bulgaria does not exceed 5%. The share of the self-employed in Greece (30%) is almost three times higher compared to the EU average of 11%. Part-time contracts are widespread in the Netherlands (50%), Austria (28%) and Germany (27%) and much less so in other EU countries (18% on average). In the aftermath of the crisis, the share of the temporary and part-time employees increased (see Figure 10, vertical axis). Thus, the issue of social protection discrepancies among different groups of workers has become even more important.

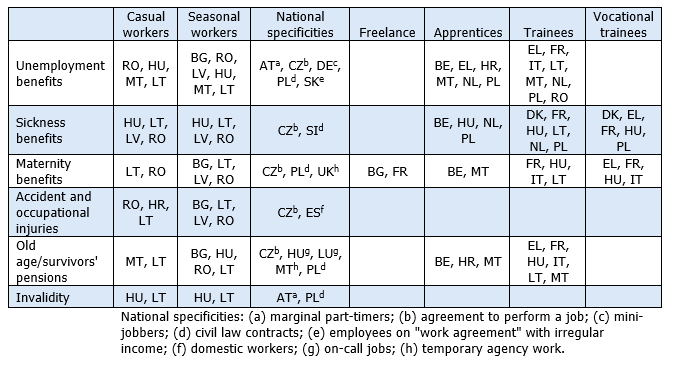

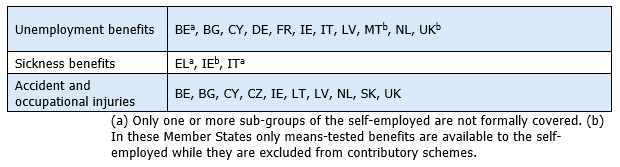

Digitalisation as well as an increase in temporary and non-standard work options requires flexicurity, i.e. a well-managed form of labour market flexibility, access to reasonable social benefits and avoiding a double disadvantage of workers with short employment spells (Eichhorst et al. (2017)). Unfortunately, in many EU countries non-standard employees and the self-employed have certain disadvantages when it comes to gaining access to social security support in case of unemployment and sickness, maternity leave, accident and invalidity benefits as well as access to old age pension (see Table 1 and Table 2). Workers are often unaware of these specific conditions.

In several EU countries, the self-employed are also excluded from the formal coverage (see Table 2). They have no mandatory coverage and cannot opt into voluntary schemes (European Commission (2018a)).

Figure 10. Temporary workers and the self-employed; % of the total number of the employed

Table 1. Lack of formal social security coverage for non-standard workers

Table 2. Lack of formal social security coverage for the self-employed

As workers' careers become less linear, the transferability and transparency of entitlements become more important. While there have been policy initiatives to address coverage gaps in several Member States, the recent proposal for EU Council Recommendation on access to social protection aims for comprehensive and systematic improvement (European Commission (2018b)). The objective of this Recommendation is to provide access to adequate social protection to all workers and the self-employed in the Member States by establishing minimum standards in the field of social protection of workers.

According to the proposed Recommendations, EU Member States should ensure that workers have access to social protection by extending formal coverage on a mandatory basis to all workers, regardless of the type of their employment relationship, while also preserving the sustainability of the system and implementing safeguards to avoid abuse. EU Member States should ensure that the self-employed have access to social protection by extending their formal coverage. The self-employed should have access to sickness and healthcare benefits, maternity/paternity benefits, old age and invalidity benefits as well as benefits in respect of accidents at work and occupational diseases on a mandatory basis as well as access to unemployment benefits on a voluntary basis.

Member States should ensure that entitlements – whether they are acquired through mandatory or voluntary schemes – are accumulated, preserved and transferable across all types of employment and self-employment statuses and across economic sectors. Member States should also ensure that any exemptions or reductions in social contributions for low-income groups apply, regardless of the type of employment relationship and labour market status.

The recommendation still has to be adopted formally, which should be done in 2019. After that, Member States will have 12 months to implement the principles and submit their action plans reporting on the corresponding measures taken at the national level. In the case of Latvia, these changes will improve the social protection of the self-employed and casual and seasonal workers, and they will normalise the social security protection of all workers.

Bibliography

ECB Economic Bulletin (2016). New evidence on wage adjustment in Europe during the period 2010–13. Issue 5, Article 2, pp. 53–75. Available from:

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/eb201605_article02.en.pdf?e47c28d61e67666aa004d023441b87bc.

EICHHORST, Werner, MARX, Paul, WEHNER, Caroline (2017). Labor Market Reforms in Europe: Towards more Flexicure Labor Markets? Journal for Labour Market Research, Springer; Institute for Employment Research/Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB), vol. 51, issue 1, December 2017, pp. 1–17. Available https://ideas.repec.org/a/spr/jlabrs/v51y2017i1d10.1186_s12651-017-0231-7.html.

European Commission (2014). Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2014. Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Directorate A, December 2014. Chapter 1. The legacy of the crisis: resilience and challenges, Section 5. The impact of the recession on labour market institutions, pp. 75–91. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=7736&type=2&furtherPubs=yes.

European Commission (2017). Structural Reforms in the Euro Area: A Selective Overview. Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Quarterly Report on the Euro Area, vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 8–10.

Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/ip060_en.pdf.

European Commission (2018a). Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2018. Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Directorate A, June 2018. Chapter 5. Access and sustainability of social protection in a changing world of work. pp. 19–20. Available from:

https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=9150.

European Commission (2018b). Proposal for a Council Recommendation on Access to Social Protection for Workers and the Self-employed. COM(2018) 132 final, 13.3.2018. 26 p. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19158&langId=en.

FADEJEVA, Ludmila, KRASNOPJOROVS, Oļegs (2015). Labour Market Adjustment during 2008–2013 in Latvia: Firm Level Evidence. Latvijas Banka Working Paper, No. 2. 178 p. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ltv/wpaper/201502.html.

IZQUIERDO, Mario, JIMENO, Juan Francisco, KOSMA, Theodora, LAMO, Ana, MILLARD, Stephen, RÕÕM, Tairi, VIVIANO, Eliana (2017). Labour Market Adjustment in Europe during the Crisis: Microeconomic Evidence from the Wage Dynamics Network Survey. European Central Bank Occasional Paper, No. 192, June 2017, 76 p. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ecb/ecbops/2017192.html.

Textual error

«… …»

Komentāri ( 1 )

Interesting.