Devaluation: Exports and Imports

For a small country like Latvia, neither theory nor global practice ascertains any gains from devaluation.

Are exporters going to benefit from devaluation of the national currency? Will devaluation lead to an improved foreign trade balance of Latvia? This article aims to discuss why theoretically positive effects from devaluation may prove short-lived for Latvia.

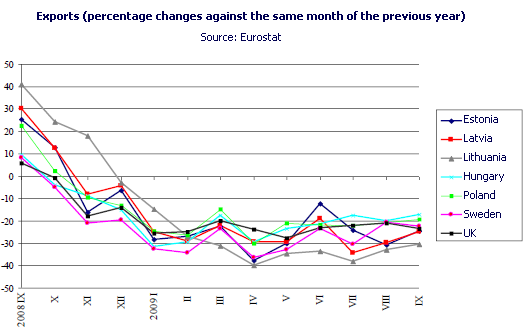

Many countries in the euro area and the European Union as a whole are sending signals of economic recovery, with real GDP recording a quarter-on-quarter growth in the third quarter following a downturn over five consecutive months. International institutions anticipate the global and euro area economic growth to gain momentum in the next year. This implies that the global external demand is gradually recovering, a positive signal for the Latvian economy as well. At the same time, in order to take advantage of the strengthening demand in other economies, Latvia's export sector should boost its competitiveness. Latvia has made its choice to follow along the path of restoring competitiveness via reducing costs, with the fixed lats peg to the euro maintained, which enables businesses to reduce costs gradually. In previous years, labour costs rose steeply due to labour shortages, almost doubling on the backdrop of insignificant productivity improvements. Would devaluation or the reduction in national currency's value be a cure-all? It must be admitted that the devaluation of Latvia's national currency may result in some short-lived gains for an individual exporting company while in no way improving Latvia's foreign trade balance. What is the correlation between devaluation, exports, imports and the current situation in Latvia? Exporters with income primarily in euros will be able to exchange euros for more lats. This is, however, only one side of a mathematical exercise, while there is the other pending as well. Imports will simultaneously become more expensive (to the extent of devaluation), and exporters' payments in lats for imported goods and inputs will increase, for the imported commodity prices will have risen automatically. Latvia is short of resources needed in manufacturing, e.g. electricity and fuel, and the exporters who would make relatively larger amounts of quick money due to devaluation would need these resources as well. Intermediate and capital goods, i.e. resources (or inputs) necessary to manufacture goods for exports, account for 60% of Latvian imports. In the event of devaluation, favourable effects needed to promote exports would be simply "consumed". Moreover, as the population's purchasing power, despite wages of the employed remaining seemingly intact, is likely to drop due to more expensive imports, businesses will be left with meagre opportunities to reduce input costs at the expense of wage cuts. There is always an alternative of encouraging people to buy domestically produced goods, yet it is not a solution to the problem of imported goods in so small a country as Latvia where imports play a very important role: in 2008, imports accounted for 55% of GDP. Not only in practice but also in theory, devaluation does not generate any gains for such economy as Latvia. Economic theory maintains that currency depreciation positively impacts exports of major economies whose resources are abundant and price setter's reputation global. While Latvia is a small open economy where this condition does not hold, other postulates regarding depreciation and its economic effects should be borne in mind. Thus, according to the Marshall-Lerner condition, for a devaluation to have a positive impact on foreign trade balance, the sum of price elasticity of imports and exports should exceed 1. Econometric evidence suggests that export and import price elasticity in Latvia is low, standing below 1, and the Marshall-Lerner condition is not met, hence a positive effect from devaluation on foreign trade balance is not to be expected. Due to structural peculiarities of Latvia's economy, currency devaluation would not support a better foreign trade balance either. As imports were almost twofold over exports as late as the end of the last year, devaluation would have resulted in more costly imports than the export revenue growth could compensate for. Even if we made a commitment to do without any imported consumer goods, which is hardly realistic, there would be no gains at all as at the end of the last year imported raw materials and manufacturing equipment alone were on par with goods exports from Latvia. In order to balance foreign trade flows, i.e. to improve the current account balance and the balance of goods and services exports and imports, Latvia does not need to depreciate its national currency, the lats. Latvia's goods and services trade balance whose deficit or the imports excess over exports accounted for 20% of GDP in 2006 and 2007, has improved notably, with costs related to goods and services imports completely covered by the income from exports. It clearly shows that the excess of imports over exports stemmed from exorbitant consumption in previous years; when the exaggerated consumption abated, imports contracted substantially. The crisis enabled businesses to adjust costs and boost competitiveness, and currently some export-oriented branches report stabilisation and growth. Has currency devaluation helped other countries? With the global financial crisis deepening, the demand for currencies of some countries, e.g. the UK, Sweden and Poland, weakened and their value dropped. Russia devalued its national currency last year by a monetary policy decision, a theoretically sound move, as the structure of Russia's economy with abundant resources significant for exports cardinally differs from the Latvian economy. Meanwhile, imports play a less important role in Russia, at around 18% of GDP. Nevertheless, amid weak global demand, in none of the countries above did depreciation bring about stabilisation in exports. According to statistical data, in the nine months of the current year, exports in all countries, fixed, floating or devalued exchange rate notwithstanding, are notably lower than a year ago. A 17% drop was recorded for Poland, 25% for Sweden, and 20% for the UK; all these countries have a floating exchange rate, and their currency depreciated in this period, even though this year a rebound has been recorded. The countries with fixed exchange rate experienced a similar drop: 19% in Latvia, 21% in Lithuania, and 19% in Estonia. In Russia, currency devaluation brought about a 46% contraction in exports. Apparently, other factors than the exchange rate are among those determining export cuts and differences across countries. Consequently, small economies in the global trade environment are price takers, and global practices show that several of them have returned to the path of economic growth not via devaluing their national currencies but by pursuing resolute economic policy programmes. In the 1980s and 1990s when Sweden and Finland devalued their currencies, no anticipated positive gains were recorded. The negative effects of several devaluation rounds in these countries were repeatedly referred to by A.Åslund, a leading expert on East European economic matters, at the Bank of Latvia conference this year. "In 1982, Denmark decided not to devalue. Instead, they decided to liberalise their economy. [..] Denmark was the pioneer among the Nordic countries in making reforms, and at that time Sweden and Finland were on a steady devaluation track which meant that they did not take care of their structural problems - they did not undertake the deregulation that was necessary to get a higher economic growth." Of the three countries, Denmark was the first to attain high living standards. It was only later that Sweden and Finland, perceiving that single and successive devaluations do not ensure a sustainable growth, undertook to implement economic policy measures, e.g. restrict wages and salaries to boost competitiveness, promote the manufacture of high valued added output, etc. When the global demand strengthened, such competitiveness-boosting measures resulted in a sustainable export growth and benefits for the respective economies, pushing up people's welfare as well. If Latvia follows this path, it can achieve export expansion and a higher level of well-being for the nation.

Textual error

«… …»