Is it time to reconsider anecdotes about slowpoke Estonians?

Anecdotes about the slowness of Estonian people appear less and less in accord with reality. The Estonians were the first nation in the Baltic region to be invited into the OECD club of developed countries; they were the pace-makers for the EU accession negotiations; they pioneered e-voting in elections via the Internet; they developed the Skype; now they have outpaced their Baltic neighbours with being the first to enter the euro area.

How did Estonians manage to succeed in accomplishing it all?

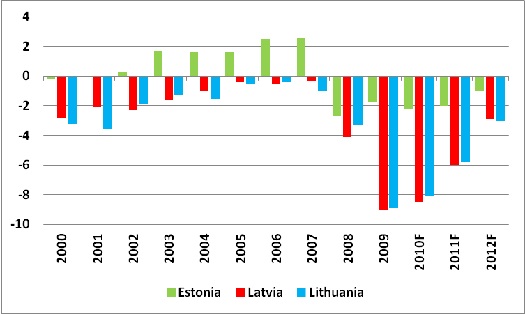

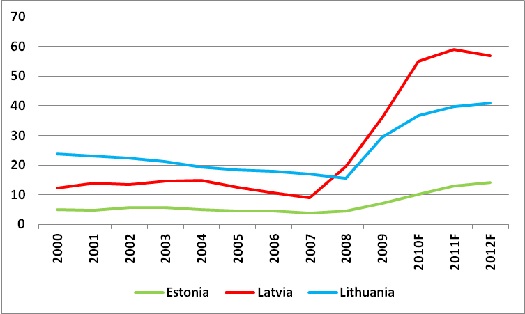

This is a result of the Estonian government's prudent economic policy or, in other words, concerted action to balance the nation's needs with the available capacities, not spending more than earning. Moreover, Estonians put the money away for a rainy day. Estonia's budget balance has been positive since 2002, with the surplus increasing until 2007 due to the economic growth (see Chart 1). The Estonian government resolved to establish a stabilisation fund as early as the beginning of 1997. It is difficult to find a non-oil-producing country living almost without any public debt but Estonia can do it: the need to boost borrowing has been eliminated by striking a reasonable balance between state budget revenues and expenditure. As a result, Estonia's public debt ranked among the lowest in the EU, at 7.2% of GDP in 2009 (see Chart 2).

Chart 1. Budget Balance (in % of GDP)

Source: State Convergence Programmes

Chart 2. Public debt (in % of GDP)

Source: State Convergence Programmes

Of importance is also the accumulated reserve which Estonia did not spend in the pre-crisis years. Not because the people did not aim at, e.g. a motor highway similar to one leading from Klaipeda to Vilnius but because of the nation's deep conviction that the financing held in reserve would help weather out an eventual crisis. By contrast, Latvia and Lithuania plunged into pure euphoria about the buoyantly rising budget revenues in the pre-crisis period and took to immediately spending them, without giving much thought to the future.

Kalev Kallemets, representing the leading Reform Party in the government, believes that labour market liberalisation along with the reasonable economic policy enabled Estonia to succeed in keeping the state budget deficit in line with the 3%-of-GDP-criteria even in the crisis period. In April of the last year, labour market liberalisation reforms were launched to enhance labour market resilience via, e.g. alleviated recruiting and dismissing terms. As a result, companies were enabled to find employees of the needed qualification sooner, and wage and salary boosts unsupported by a similar growth in productivity and efficiency were curbed. Enhanced resilience of the labour market, in turn, improved competitiveness, attracted new investors, and pushed up tax revenues.1 Similar reforms have not been initiated in Latvia and Lithuania as yet.

The Estonian tax discipline is worth a mention. Tax decisions are more stable and lasting: they are not often amended or altered. The Estonian tax system with a similar tax rate for both households and corporations is easy to run and comprehend thus making life easier for investors and businesses. Meanwhile, the 2010 Corruption Perception Index recently compiled by Transparency International demonstrates that in terms of corruption Estonia, with the index at 6.5, is the cleanest of all Baltic countries (index at 5.0 for Lithuania and 4.3 for Latvia), which is quite meaningful for making investment decisions. Compared with Latvia, investors see Estonia as a country with much sounder environment for long-term investment in production, given FDI in manufacturing in the amount of 10% of GDP in Estonia at the close of 2007, i.e. prior to the crisis, and 3.5% in Latvia; such FDI flows ensure not only long-term economic growth but also enhance stability in the periods of crisis and related financial outflows. The Estonian government holds its property in good control as well: dividends exceed the amounts collected elsewhere in the Baltic States.

This obviously reasonable and tight fiscal policy paved Estonia's way to the euro, and it should be noted that ultimately not only the state but also every citizen will benefit from it. This year the nation has to make debt servicing payments from the budget in a lesser amount than last year, which means larger appropriations for other public needs. In addition, even though during the crisis Estonia was among those to carry out fiscal consolidation (both by cutting expenditure and raising taxes), public confidence in the government remained high: according to a Eurobarometer survey, 47% of total population confide in the government, ranking Estonia in the eighth top position among the EU27 group. The attainments in providing stability so far, in budgetary and tax policies in particular, support the recovery from the crisis as well: after bottoming out, the growth in Estonia's GDP is the strongest of all Baltic States.

Estonia has implemented other progressive reforms as well. While the Lithuanians were only dreaming about an electricity grid with Poland and Sweden, the Estonians developed one with Finland as early as in 2006. Significant reforms have been implemented also in the sectors of electronics and telecommunications.

What are Lithuanians doing?

Lithuania came close to the euro introduction in January 2007 but failed due to the inflation criterion. The update of the Lithuanian euro changeover plan on 25 April 2007 ended with no changeover date specified; 1 January 2014 is the most often referred date in public discussions. Lithuania's President Dalia Grybauskaite, Lietuvas Bankas Governor Reinoldijus Šarkinas and many economists maintain that the road to the euro is not a goal but rather a means to ensure economic sustainability. Closely watching Estonia's achievements, the Lithuanians are doing their best to improve the budget balance. It would lead to better sovereign credit ratings, sustainable economic growth and euro introduction. As the Lithuanian government is considering borrowing from international financial markets in 2011, improved credit ratings and sustainable economic recovery are of particular importance. If the winning parties at the 2012 parliamentary election proceed with fiscal consolidation, Lithuania's prospects for introducing the euro as early as 2014 will be up.

How is the euro introduction in Estonia going to affect Latvia?

As meeting the Maastricht convergence criteria giving green light to the euro changeover testifies to the country's ability to ensure stability, foreign investors are most likely to give preference to Estonia as a territory in the Baltic Region with a more stable investment climate. Higher credit ratings assigned to other countries after the euro adoption confirm it well, and Estonia boasts of notably improved ratings already now. The adverse effects on the Latvian economy, e.g. investment flows in favour of Estonia, may be offset by the pursuit of such economic policies in Latvia that would explicitly demonstrate Latvia's commitment to stabilise its economy, improve the investment environment, and adopt the euro. It should be noted, however, that the gap between the economies of the Baltic States is not too deep as yet, and foreign investors, upon considering their investment options in the manufacturing sector of the Baltic States, may also take into account the factor of costs, as, e.g. wages and salaries in Latvia and Lithuania are lower. But if Latvia fails to introduce the euro on the projected date in 2014, its credibility would fall and risks for Latvia to become a periphery of Europe without new investment and business opportunities would emerge.

The next channel of Estonia's impact is favourable for Latvia: the growing income due to the adoption of euro in Estonia is likely to have a positive effect on its neighbouring countries in terms of new investments from Estonia. So far the flow of direct investment from Estonia has been the strongest towards Lithuania (according to the June 2010 data, 28% of accrued Estonian direct investment abroad), while Latvia ranked second with 26%. Taking into account the already established export ties between Latvia and Estonia and the fact that Estonia is the second largest export trade partner of Latvia (14% of total Latvia's exports go to Estonia), the growth in Estonia may boost the demand for Latvia's exports.

The Estonian success story teaches us a good lesson: the set goals can be attained via well-defined vision and strict discipline. During the crisis Latvia managed to brace up and take a longer perspective: due to the cuts in state and businesses expenditures the ability to compete, as captured by export growth and growing market shares of Latvian exporters, is reviving. The first two quarters of the year, and likely so the third quarter as well, saw the economic growth to recover. If Latvia proceeds with the on-going fiscal consolidation by implementing the reforms that aim at sustainable growth and long-term fiscal discipline, Latvia's future will become more secure and the changeover to the euro in 2014, primarily anticipated by Latvia's businesses and investors – creators of jobs and tax revenues, more realistic.

1 Source: Veidas, Lithuanian magazine, June 2010.

The article was published on the internet site Delfi on 9 November 2010.

Textual error

«… …»