Is one foot of Latvian economy in the middle-income trap?

Looking at the recent gradual moderation of the growth rate of Latvian economy (although largely on account of external developments that are outside the focus of this article), I keep returning to the issues which were topical for me in the pre-crisis period. That was the first time I came across the concept of middle-income trap (MIT).

I believe this concept is well known to economists, though slightly forgotten of late, since it has not been significant for some time (at least in case of Latvia). So what is MIT actually? This notion implies a situation when in the course of real convergence an economy is stuck at the level of middle income and is incapable of advancing to the next, higher-income level.

Quite a lot of economic literature has been dedicated to the above phenomenon; nevertheless, there is no absolute explanation and/or solution for avoiding or overcoming it. At the time when my career as an economist had just begun and Latvia's economy converged towards the average level of the European Union (EU) at an accelerated pace, I was contemplating on the potential possibility for Latvia to catch up with the EU average level. There are various economic growth theories researching the above issue, but let's leave it for some other time.

According to Eurostat, in 2013 Latvia reached 67% of the EU average GDP per capita, expressed in purchasing power parity, i.e. GDP is adjusted taking into account the different price levels in the Member States, thus providing more accurate characteristics of the economic growth, the purchasing power and well-being of the population. It can certainly be argued whether such an indicator comprehensively reflects the real convergence process and the methodological details of the indicator may be questioned, but that would be the easiest way since there are no real alternatives for this indicator. Some time ago, during the years of accelerated growth in particular, it was quite popular to apply a linear trend to calculate the number of years Latvia would need to catch up with the EU average. This is certainly a very simplified approach, more suitable for politicians, while the economic theory suspects some problems there, such as MIT.

What is a middle-income trap?

As a rule, the first steps for countries on their road towards real convergence are quite successful. The first stage of the economic development is associated with the use of their natural advantages – utilisation of their natural resources and agricultural lands.

At the next stage the lowering of the barriers of external trade and capital flows relatively quickly provides an essential contribution to the real convergence: the development of labour-intensive industry (e.g., manufacturing of wearing apparel and textiles, food products, basic wood industry, etc.) gradually begins.

At the subsequent stage foreign direct investment (and its spill-over effects), exports (mostly based on relatively cheap labour and minor processing) and imports (inter alia, the technology and know-how transfers) continue to facilitate the process of real convergence at a rapid pace. A gradual rise is observed in exporters' income, and the local manufacturing develops along with the services necessary for servicing its sectors. An increase in labour income also persists (which often exceeds the increase in productivity growth rate), resulting in a more expensive and consequently less competitive output. With wages and salaries in the tradable sectors moving up, the demand for services provided by the service sectors also gradually improves, thus pushing up wages and salaries in the latter as well. Investment in capital goods, i.e. more effective equipment, and/or innovations moving the manufacturers up the value added chain enables the development and further convergence of the economy. With the rise in labour income persisting and the gap between the convergence target groups narrowing, the competitive advantages (mostly those related to price factors) continue to undergo erosion until the moment when further development based on the existing economic resources is limited.

The process of real economic convergence can be compared to an athlete beginning his/her training, e.g. in the long jump. It does not take much effort to learn how to make a one metre jump; the same is true of jumping two or three metres – just have a look at how others manage that. To make a four-metre jump, one has to practice and will probably end up with some bruises. To succeed in jumping five metres, one is likely to work with a coach to improve the jumping technique, and each subsequent centimetre will require hard work and strain.

It holds true for the economy as well: upon reaching a certain limit of real convergence, the fundamental factors of economic growth (mostly geographical advantages, labour skills, natural resources, etc.) are depleted. The wage gap between a certain country and its external trade partners narrows and no longer provides advantages in maintaining competitiveness in manufacturing and exports. It may happen that at this moment the economy in a way "gets stuck" at the level of middle income, with no chance to advance to the next high-income level. Just like in the case of the athlete, it is necessary to work hard and polish the details in order to achieve the next improvement.

Being stuck in MIT means that the advantages provided by price competitiveness have obviously deteriorated in comparison with the initial stage of real convergence. An increasingly important role is played by such non-price factors as the quality aspects of goods and services, as well as consumer preferences (for non-price competitiveness of Latvia see the recent research by my colleague K.Beņkovskis).

Recent years have seen lots of articles, publications and research papers on MIT. Some of them tend to be more descriptive, others are empirical. Studies of relevant literature suggest that no uniform understanding has been reached as to what MIT is and what signs testify to its existence. Essentially MIT is nothing extraordinary: it is just a name introduced by economists for one of the stages of the real economic convergence process. The economists and researchers of the World Bank are quite focused on MIT: there are several publications (see the list of reference literature at the end of the article) explaining both the essence of MIT, the empirical results regarding its causes, and the potential solutions. My personal favourite is the classification of factors behind the MIT by Akio Egawa, a researcher of Bruegel think tank (see A.Egawa, p.4).

In his working paper on the relation of income inequality to MIT he defines the causes behind MIT and differentiates them from the economic slowdown factors, as many of the latter may just testify to a simple downturn in the economic cycle rather than to the existence of MIT.

In his opinion, the major factors causing an economy to fall in a MIT are as follows: an increase in wage levels (to put it in other words, "a rise in wages and salaries incommensurable with the productivity growth rate"); excessive public investment (hampering private investment growth); high dependence on exports (or rather a small domestic market); regional income disparity; household income inequality; population ageing.

Although part of the factors mentioned by Egawa are also associated with a downturn phase of a simple economic cycle, in my opinion, it is the set of the above factors that adequately describes the very essence of the word "trap". Namely, of this set of factors for a hypothetical economy open to external trade, the rise in wage levels has lead to restricted price competitiveness, and the population ageing, weak governance and implementation of the structural policies, limited both by the political will and economic principles, i.e. government budget constraints, prevents it from advancing to the next income level. Hence the economy is in a way caught in a trap that it cannot escape from without serious "cuts".

Europe and MIT

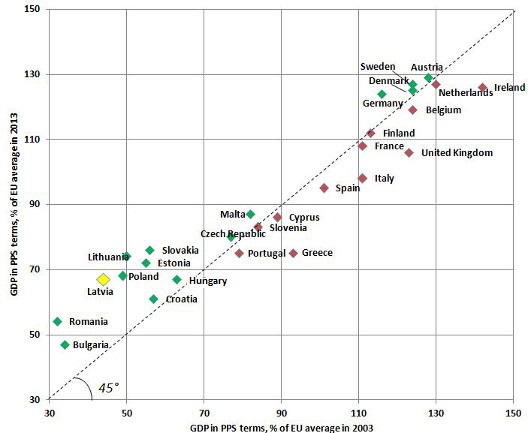

As mentioned before, it is difficult to provide an unequivocal assessment whether the economy is in the MIT. Nevertheless, out of pure interest I had a look at the real convergence process in the EU-28 Member States, particularly focusing on the countries that joined the EU together with Latvia in 2004. Chart 1 shows a diagram where the national GDPs per capita are expressed as per purchasing power parity in 2003, i.e. before the "great" EU enlargement, on the horizontal axis and the same national indicators after a decade in 2013, on the vertical axis. The countries above the dotted 45° line had improved their relative well-being in the above time period, while those below the line faced a decline. The farther the national indicator is from the 45° line, the greater the changes in the respective country over the ten years.

Chart 1. GDP developments in EU 28 Member States in 2003–2013 [1]

(click to enlarge)

Data source: Eurostat

The chart shows a pronounced division of the countries in groups: most of EU-15 (the so called "old Member States") are in the high-income group. The only exceptions are Greece and Portugal whose relative level of well-being has declined in the above decade. They are followed by a group of countries having joined the EU in 2004 and Croatia who joined the EU only in 2013. Of them, Malta and the Czech Republic enjoy the highest level of well-being; however, the most pronounced well-being growth in comparison with 2003 is observed in Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Estonia and Slovakia, while Croatia, Hungary, Cyprus, the Czech Republic and Slovenia have achieved relatively small progress (or even regress) during the decade. As regards the above countries, we may probably refer to MIT, but each of them would certainly have its own specific reasons, e.g. in the case of Cyprus, it is the crisis of early 2013. Another group comprises Romania and Bulgaria having joined the EU in 2007.

Portugal, Ireland and MIT

Speaking about real convergence and MIT in the EU context, Portugal and Ireland are usually mentioned. These two countries are similar enough for comparison; however, their performance has differed notably over the last few decades. Just some decades ago Ireland and Portugal enjoyed approximately the same level of well-being; in 2013, however, Ireland was among the EU countries with the highest level of well-being, whereas Portugal had stuck at around 75% of the EU average. Slovakia, Lithuania and Estonia have actually caught up with Portugal in terms of well-being. It is Portugal that is usually mentioned as a classic example of MIT in the EU when an economy is not capable of advancing to the next stage in its development. Weak political will and inability to carry out effective and timely structural reforms are factors having affected Portugal's development over time, while Ireland has been capable of politically decisive action, pursuing economic development based on structural reforms.

The substantial differences between the above countries were also manifest in the recent sovereign debt crisis when they both had to turn to the international institutions for help. Ireland's action under the assistance programme was fast and decisive, resulting in a quick closure of the programme and the country's return to international financial markets. At the same time, the assistance programme for Portugal has been essentially more complex and at this stage it is not quite clear yet whether or not Portugal might be in need of another one.

When speaking about MIT in global terms, two contrastive factors are usually confronted: the success achieved by the Southeast Asian economies and the problems faced by the South American countries. The major debate questions why several Southeast Asian economies have managed to cope with the MIT but South American economies haven't. By the way, if you study recently published articles/research papers on the above issue, you will inevitably come across publications discussing China's potential falling into MIT…

Has Latvia already reached the middle-income trap?

Nothing is just black or white in the economy; hence it is also quite difficult to answer this question. The overall road of real convergence that Latvia has taken to this point is similar to the process characterising MIT. It is difficult to provide an unequivocal assessment of the historical process of real convergence due to the numerous economic shocks that time and again stopped the convergence process (the banking crisis, the Asian-Russian crisis, the crisis of 2008). Nevertheless, Latvia has undoubtedly achieved substantial convergence during the period of its independence. Thus in 1995 Latvia's GDP in terms of purchasing power parity accounted for a mere 31% of the EU average, whereas in 2013 it had already reached 67% (the indicators are not fully commensurable, as the number of EU Member States has also increased notably, thus reducing the average level of well-being.

In the beginning, Latvia like most of the emerging economies started with market liberalisation, lowering of various external trade barriers and implementation of structural reforms. The above measures soon facilitated the process of real convergence. Between 1996 and 2003 the real GDP of Latvia grew by 6.0% on average: despite various economic shocks, it was an essential convergence process. In the next four years the real growth rate increased to 10.1%, ensuring an extremely fast process of real convergence, at the same time generating a number of economic imbalances that stopped the on-going success of real convergence for three years. However, in 2011–2013 Latvia recovered its economic growth (4.6% on average), continuing its gradual convergence towards the EU average.

The short answer to the question as to whether Latvia is already in the MIT is no, it isn't. In my opinion, several signs testify to that:

1) Latvia's export share in global imports continues to grow. Latvian exporters keep entering new markets, thus demonstrating the competitiveness of Latvian exports. In the MIT context, there is a particularly positive feature: the improvement in Latvia's competitiveness is mostly driven by non-price factors, which is one of the major preconditions for overcoming MIT.

2) The profitability ratios of Latvian companies, expressed as profit or loss after taxes against net turnover, do not suggest any signs of decline, i.e. despite the relatively rapid rise in average wages and salaries, businesses are at least able to maintain their previous profitability ratios. However, a negative trend in manufacturing was observed in relation to the above in 2013 (please see my monthly comment on the sector's indicators).

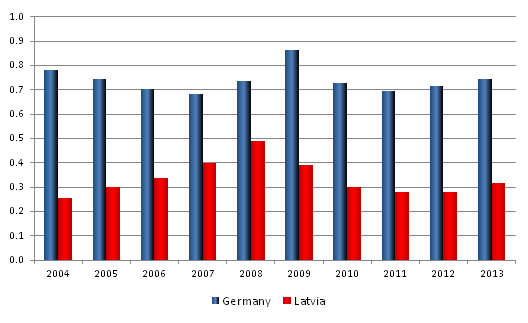

3) The level of remuneration gap with the euro area remains high. Although the average rise in wage level in Latvia exceeds that in the EU, quite notable differences persist (see Chart 2), suggesting that Latvia still has a potential of price competitiveness, also supported by a relatively rapid profitability growth. At the same time, it is obvious that with the remuneration gap narrowing, Latvia's price competitiveness will also weaken. As regards, for example, the dynamics of Latvian and German unit labour costs in manufacturing (I chose Germany as one of the core EU member states; unfortunately, no aggregate information on the EU average is available), Latvia is gradually approaching the levels observed in Germany; nevertheless, the differences are substantial enough to keep us from worrying, at least for some time.

Chart 2. Unit labour costs in Latvia and Germany [2]

Data sources: Eurostat and the author's calculations.

At the same time, we cannot deny the signs in Latvia's economy suggesting that Latvia might fall in the MIT in the medium term. Household income and regional disparities are quite pronounced in Latvia; population aging is also observed. Lack of innovation/research and development, weak governance and human capital development, as well as weakness of reforms in the education and health sectors can also be mentioned as descriptive factors. Up to now the use of the fundamental growth factors of Latvia and the pronounced difference of labour costs in comparison with the EU allowed for successful convergence; however, at some point (I am not sure whether at 70% of the EU average level or more) that will not be enough: further growth will require sound other factors, inter alia institutional ones. At this stage I am not sure whether the current government's long-term planning is focused on preventing the MIT issue becoming a problem for us. Mostly the current fires are being extinguished, while little is done towards the long-term development. In the government long-term planning documents the real convergence process is most often perceived and shown as a linear process, i.e. trend growth. The possibility of linear real convergence cannot be denied; however, the measures taken to ensure it to date are not too convincing. Can we trace the moment when Latvia is about to fall in the MIT? It is difficult to give an unequivocal answer: intuition suggests we still have at least five to seven percentage points of real convergence (expressed as the ratio of GDP per capita, based on purchasing power parity, to the EU average), so it means at least several years. In such a case Latvia would have reached approximately 75% of the EU average.

The estimates of potential GDP is in a way a similar concept for prompting the moment when Latvia could fall in the MIT. Although calculations of potential GDP are very theoretical, they provide a good insight into the long-term potential of the economy. The potential GDP estimates are mostly based on the Cobb-Douglas production function, which takes into account the amount of accumulated capital (investment), the labour and demographic contribution, as well as the total factor productivity (TFP) which in turn describes factors that cannot be measured directly: technological progress, know-how, developments of human capital and institutional factors, etc.

As mentioned before, the calculation of potential GDP is technically challenging and subject to essential historical revisions. No doubt, however, that the estimate of the potential GDP growth of the Latvian economy will decline in the next decade, irrespective of the institution estimating the above indicator. The negative demographic trends mostly account for that (see a research by my colleague A.Meļihovs on demographics of Latvia), while an increase in the accumulated capital is limited by the weak investment growth. The dynamics observed over the last few years shows that investment activity in Latvia is low at this stage. Maintaining the potential GDP growth level within the range of 3%-4% will require more rapid investment growth in comparison with the one currently seen in data. As to the total factor productivity (TFP), it may increase only subject to structurally better investment, i.e. technologically more advanced, more targeted, etc. investment. Moreover, the TFP should improve on account of successfully implemented structural reforms.

With respect to the potential GDP, of the three variables (labour, capital and TFP), a relatively rapid impact (though we are still talking about years) is possible on only two of them – capital (investment) and TFP (structural reforms). Demographic trends can be influenced, yet their effects are to be expected in decades. It is also almost impossible to boost the accumulated capital rapidly: it is a result of high investment activity lasting for several years.

Hence TPF is the only variable that can be affected; it essentially points to the capability of the economy to combine the above two factors – labour and capital, making use of the technological progress, education, health and other factors crucial for economic growth. TPF may be influenced by a number of factors, with the institutional (soundness of the legal environment, bureaucratic barriers, barriers associated with start-up and winding up of businesses, etc.) and technological (technological progress, cooperation of the industrial sector with research centres, etc.) factors being the main ones. Thus it is up to each and everyone to judge about the chances to escape the MIT.

How to avoid/cope with MIT?

In my opinion, productivity growth is the major factor supporting sustainable growth of the Latvian economy. It seems the contribution of the demographic developments to the economic growth will be neutral in the near future (in case of the best scenario). Essentially it means that further economic growth is possible only on account of an increase in productivity. How to raise productivity? The three factors mentioned below partly answer the question. There is a lot to do, but, in my opinion, priorities are as follows:

1) One of the potentials underestimated so far is more serious consideration of the energy issues. The issues of energy dependence and tariffs have been sufficiently addressed and discussed. As a result of the pressure from manufacturers, the economic policy makers sooner or later are likely to decide on reducing this burden on the operation of energy-intensive industries. There is an aspect, however, which has been less considered – it is energy efficiency. Here I mean manufacturing and the commercial sector with a huge hidden potential rather than households. Benefits gained by companies implementing energy efficiency measures serve as a proof to the above. In my opinion, we should start developing this sphere by promoting the availability of energy audits both by ensuring their availability and information about them. I don't think manufacturing companies are fully aware of the potential of raising energy efficiency.

2) It is no news that reforms should be implemented in the education sector. However, I'd like to add a slightly different aspect of this issue. Discussions with entrepreneurs and business organisations have resulted in the conclusion that it is extremely necessary to improve the prestige of the vocational education in the eyes of the general public as such rather than in legislative acts and planning documents. It seems the opinion that the vocational education, i.e. the vocational secondary schools, technical schools and colleges, is just meant for those who have failed in their studies, is still deep-rooted in Latvia. However, we have come to the stage when top-level professionals in selected manufacturing companies can earn wages close to the levels earned by manufacturing managers.

3) Latvia is still among the European countries that are negligent with respect to science, research and innovation. Latvia still can be found at the bottom of the various lists describing R&D and innovation performance. For example, European Commission has updated Research Excellence indicators, and Latvia is still hugely underperforming. It is an important issue because as I wrote some paragraphs above – TFP, the only growth factor which can be influenced by economic policy in a direct manner, relies mainly on the success of innovation and R&D. In recent years the first steps to tackle the problem have been taken by economic policy makers (National Reform Programme of Latvia), but due to limited fiscal space and also political will, the reforms have been slow and lack complexity.

While writing this article, the idea whether it is not too late would not leave my head. "It is never too late", that's the simple answer. However, the feeling that Latvia's economy has started its course towards the MIT wouldn't leave me, and unless measures are immediately taken, it will be difficult to follow the scenario of sustainable real convergence.

There is no uniform recipe for overcoming the MIT; however, it is clear that the first question to be considered is how to achieve productivity growth in the future. Sooner or later the price competitiveness will obviously decline; if we retain our current position with low or medium value added in exports, our income will also be the same.

To achieve persistent real convergence in the long term, we must make a qualitative leap in the output and export structures of our tradable sectors. However, to use a metaphor, the awareness of the height of the mountain we have to climb is the main thing. The economic policy makers should understand that sooner or later the period of linear growth will come to an end, and sometimes decisive and unpopular decisions are necessary for the sake of a brighter future.

References for MIT:

- World Bank Working Paper "Middle-Income Traps: a Conceptual and Empirical Survey", 2013: http://goo.gl/rQkQ7u

- World Bank publication: "Avoiding Middle-Income Growth Traps", 2012: http://goo.gl/5YY6qD

- Bruegel Working Paper: "Will Income Inequality Cause a Middle-Income Trap in Asia?", 2013: http://goo.gl/u8lHeA

[1] For a better arrangement of the chart, Luxembourg has been excluded as its indicators are outside the scale.

[2] Unit labour costs – costs required for producing one unit of output. The value added has been adjusted with a time series of the purchasing power parity to provide a better reflection of price level differences in both countries.

Textual error

«… …»